When Nvidia Is No Longer the Only Answer: What Should Investors Really Be Worried About?

Nvidia's strategic partnership with OpenAI has shifted, with its planned $100 billion investment now contingent and potentially reduced to $20 billion amidst new funding rounds from Amazon and SoftBank. This change diminishes Nvidia's influence, as competitors like Google and Anthropic increasingly adopt custom ASICs over GPUs. OpenAI is exploring alternative inference chip providers due to performance concerns, further signaling a move away from single-vendor reliance. While Nvidia's next-generation Rubin platform offers significant performance and deployment advantages, and potential H200 exports to China offer a revenue boost, structural threats from ASICs and tighter AI CapEx growth post-2026 remain key investor concerns.

In September last year, Jensen Huang and Sam Altman announced a market-shaking strategic partnership: Nvidia would provide OpenAI with 10 gigawatts of computing capacity and invest up to 100 billion dollars. In that moment, the market broadly believed that the throne of the AI era would be shared by these two companies.

Yet just two months later, the plot flipped. An SEC filing in November showed that none of that money had actually gone out the door. The drama escalated further at the end of January this year, when Jensen Huang, pressed by reporters in Taiwan, directly denied the whole premise: “We never planned to invest 100 billion dollars. That was never a commitment.” His tone was not casual, but carried a kind of reluctant clarification. The reality is that OpenAI did invite Nvidia to invest up to 100 billion, but any investment would proceed step by step, contingent on progress.

Source: Yahoo News

Wait a second—just four months ago, that 100‑billion‑dollar announcement was greeted with euphoria on stage. How did it turn into something so awkward to talk about? What exactly happened in between?

This Wasn’t Just a Deal Falling Apart. The Power Structure Changed.

The answer lies in OpenAI’s latest funding round at the start of 2026. According to Bloomberg, Nvidia is currently in talks to invest around 20 billion dollars in OpenAI; if it goes through, it would be Nvidia’s single largest investment in the company. At the same time, the total target size for this OpenAI round is up to 100 billion dollars, with Amazon potentially putting in as much as 50 billion and SoftBank up to 30 billion. In other words, Nvidia’s real contribution is now likely closer to one‑fifth of the original “up to 100 billion” headline figure.

See the problem? In this round of financing, Amazon and SoftBank would wield far more influence than Nvidia. If OpenAI goes public in 2026—as preparations are already under way—its board will likely be dominated by these major shareholders, rather than Nvidia.

More importantly, Amazon, as the parent of AWS, cannot sit idly by while OpenAI relies entirely on GPUs supplied by another vendor. It will push OpenAI to adopt its own Trainium chips, or at least keep a balanced, multi‑vendor setup. That means Nvidia is shifting from the central nervous system of the AI ecosystem to just one of several suppliers.

That’s why Jensen Huang seemed so uncomfortable in Taiwan. This wasn’t a simple case of a business deal falling through; it was Nvidia losing the upper hand in the AI power game.

OpenAI Is Looking for a Backup Plan — But the Real Problem Runs Deeper

A Reuters report in February made this trend even clearer. OpenAI has grown dissatisfied with the inference performance of some of Nvidia’s latest chips, especially for workloads such as software development and AI‑to‑software interactions, where responsiveness is critical. So starting last year, OpenAI began exploring alternatives, talking with startups like Cerebras and Groq. They focused in particular on architectures that pack large amounts of embedded SRAM onto a single chip, with the aim of handling roughly 10% of their future inference workloads. The theory is straightforward: by reducing access to external memory, these chips can speed up inference.

Of course, OpenAI will still rely on Nvidia GPUs as its main workhorse. But the very act of seeking a “backup” supplier is telling enough: even Nvidia’s most important customer is actively working to reduce single‑vendor dependence.

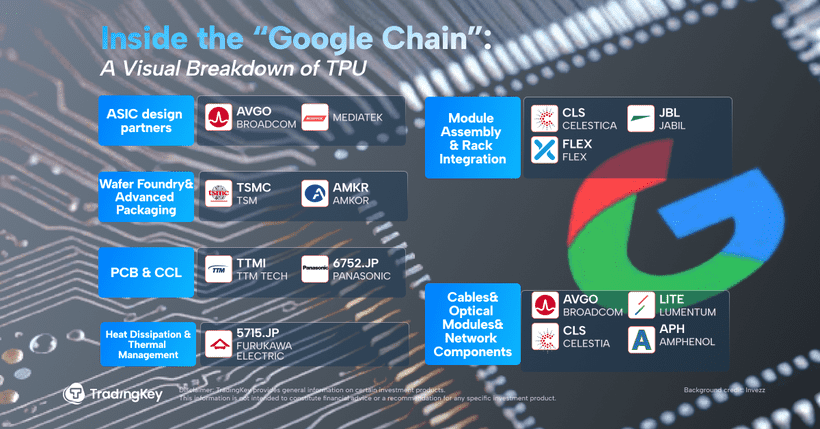

Yet this still isn’t the core threat. The real headache for Nvidia comes from competitors that bypass GPUs altogether.

The Three Kingdoms of Foundation Models: Only OpenAI Still Relies Mainly on Nvidia

Over the past two years, foundation models have taken turns dominating the headlines. Last year, ChatGPT was the undisputed star. Then Google’s Gemini came out of nowhere to steal the spotlight, and now Anthropic’s Claude has become the new favorite. But few people pay attention to the fact that each of these companies has a completely different chip strategy.

OpenAI still primarily uses Nvidia GPUs (even as it searches for alternatives). Google’s Gemini runs on its in‑house TPUs. What about Claude, the current darling? Anthropic uses a combination of Google TPUs, Amazon Trainium, and Nvidia GPUs, allocating workloads flexibly across them. This multi‑cloud strategy improves efficiency while avoiding dependence on any single supplier, and Nvidia is just one of several options.

Put differently, among today’s hottest AI models, two are powered mainly by ASIC‑style custom chips, and only OpenAI still relies primarily on Nvidia.

Many investors believe that no matter who wins in the model race, Nvidia will profit. The reality is harsher: the eventual winners are increasingly using their own ASICs to eat into Nvidia’s market. That’s the game companies like Google and Amazon are playing—using ASICs to secure supply‑chain control while pushing down costs. For Nvidia, this is a long‑term, structural threat.

Jensen Huang’s Regret

In a recent interview, Jensen Huang made a remark loaded with meaning. He said that if he could go back, he would have made different choices with Anthropic. At the time, Anthropic wanted to partner closely with Nvidia but also needed financial support, and Nvidia simply couldn’t afford it. Amazon and Google, however, could.

On the surface, it sounds like a lament about financial constraints. But what he is really saying is this: we let Amazon and Google walk away with one of the most promising customers in the space.

Anthropic became one of today’s hottest AI companies largely because of the capital backing from Amazon and Google. That funding gave it the resources to develop custom ASICs and, crucially, to lean heavily on Google’s TPUs—sidestepping Nvidia GPUs in the process. Had Nvidia invested in Anthropic early on, Claude might still be running primarily on Nvidia hardware instead of becoming a competitive threat.

That’s why Huang’s “regret” feels more like a lingering grievance. He didn’t just lose a big client; he lost a chance to reshape the landscape of the entire industry. And that missed opportunity is still echoing through the AI power game.

The Real Bottleneck: Not Who Can Make Chips, but Who Can Afford Them

From last August to now, Nvidia’s share price has barely budged—while the Philadelphia Semiconductor Index is up about 40% over the same period. Nvidia has significantly underperformed.

Source: TraingView

The irony is that Wall Street’s earnings expectations for Nvidia in 2026 are sky‑high. Some institutions are now modeling more than 9 dollars in EPS for this year, well above the roughly 7.75 dollars reflected in market consensus. Yet even such lofty earnings forecasts haven’t translated into strong buying interest.

That’s because the market is no longer focused on who can manufacture chips, but on who still has the balance sheet to buy them. The bottleneck for AI has shifted from the supply side to the demand side.

Oracle’s predicament is the best illustration. The company has roughly 523 billion dollars in remaining performance obligations on its books, about 300 billion of which are tied to OpenAI. But to fulfill those contracts, Oracle would need to commit at least 350 billion dollars in IT capital expenditures.

The reality is brutal. Oracle’s debt‑to‑equity ratio has soared toward 500%, and its latest quarter showed negative 10 billion dollars of free cash flow. In December 2025, Blue Owl Capital—originally slated to be the key funding partner for a planned 10‑billion‑dollar, 1‑gigawatt data center in Michigan—walked away from the deal, something almost unthinkable in an already aggressive credit environment. Oracle’s stock has given back the 36% surge it enjoyed in September 2025, and its five‑year CDS has hit record highs. Morgan Stanley has cut its 2030 EPS forecast to roughly half of Oracle management’s previous long‑term target. That kind of “50% haircut” from a major broker only amplifies market anxiety and pushes many investors to simply dump Oracle first and ask questions later.

All of this pressure inevitably spills over to Nvidia. If Oracle can’t pay, Nvidia’s backlog turns into empty promises. And then there is OpenAI itself, whose finances are also on shaky ground: annual revenue is around 20 billion dollars, but its annual compute bill runs closer to 60 billion. The gap can only be filled by constant fundraising.

Nvidia’s Positives: Can Its Three Cards Save the Day?

Under these pressures, Nvidia still has a few cards left to play.

First card: Vera Rubin’s technical leap

Nvidia’s response is clear: accelerate the product roadmap. When Blackwell launched in 2025, its ramp‑up issues weighed on the stock, but Nvidia learned from that episode. The next‑generation Vera Rubin platform is slated for mass production in the second half of 2026, and management has stressed that the production ramp should proceed much more smoothly.

The performance gains are striking. Compared with Blackwell, Rubin delivers roughly 3.5 times the training performance and up to 5 times the inference throughput, while cutting the cost per token on the inference side by as much as 90%. But the most important—and often overlooked—improvement lies in deployability: where assembling and maintaining a rack of Blackwell‑based systems might take more than an hour and a half, Rubin’s modular tray design and cable‑free configuration can compress that process to about five minutes, boosting assembly and maintenance efficiency by up to 18‑fold.

In practical terms, this means customers can deploy capacity faster, shorten data‑center build cycles, and materially reduce total costs. This shift in manufacturability and operability is a real competitive advantage. It is not just about raw performance; it is about economic viability.

Channel checks suggest that customer enthusiasm for Rubin is far stronger than for competing platforms, and that the transition from Blackwell to Rubin may happen faster than the market expects. Even as AMD and Broadcom grow rapidly, Nvidia’s incremental quarterly revenue remains materially higher than the total incremental gains of most of its rivals.

Of course, technological leadership alone cannot fully neutralize the structural advantages of ASICs. For giants like Google and Anthropic with in‑house design capabilities, ASICs can deliver better cost‑performance for specific workloads and offer tighter control over supply chains. But Rubin at least helps Nvidia defend its position in the GPU segment and buys time for other strategic moves.

Second card: H200 exports to China

On January 13, the Trump administration approved exports of H200 chips to China. On the surface, this looks like a major positive, but the fine print matters.

The conditions include a 25% tariff, a 50% cap on total volume, and mandatory third‑party U.S. lab verification for all chips. Taken together, these hurdles mean that actual revenue realization could be far smaller than headline order figures suggest.

Reports indicate that Chinese tech giants are preparing to place up to 14 billion dollars’ worth of orders. But once tariffs, volume limits, and approval processes are factored in, the portion that converts into revenue may be less than half of that. Policy stability is another open question. Domestic AI‑chip players in China are catching up quickly, and over the long run, Nvidia’s market share in China is likely to keep eroding.

Even so, this is still a tangible revenue stream. On a base as large as Nvidia’s, an extra 14 billion dollars in potential orders—even if only 6–7 billion ends up as recognized revenue—could provide a meaningful boost to 2026 results.

Third card: strategic investing to build the ecosystem

Nvidia is not only a chip supplier; it is also an investor in OpenAI, CoreWeave, Anthropic, and even Intel. That understandably raises questions in the market: is this circular financing?

Take CoreWeave, the most controversial name in this discussion. Nvidia’s investment there is pure equity, not debt. It is not extending vendor financing or offering cheap credit; it is buying shares at market terms. If the business succeeds, they all profit; if it fails, Nvidia takes a hit like any other shareholder. That is fundamentally different from supplier financing that inflates sales via extended payment terms or subsidized loans.

Management’s argument is that the scale of AI infrastructure investment now exceeds the capital capacity of any single company. Without equity capital from players like Nvidia, many projects might never get off the ground. This is what they call strategic investment. Nvidia’s long‑term vision imagines its own revenues reaching one trillion dollars annually by the end of the century, with the broader ecosystem creating far more value, and Nvidia wants a meaningful piece of that as an owner, not just a vendor.

That said, investors find it hard to completely trust the purity of reported growth when they see Nvidia injecting capital into customers who then turn around and buy Nvidia chips. Those concerns have become a major overhang on the company’s valuation. Yet from a purely economic perspective, in an era when capital for AI is extremely tight, this kind of ecosystem investing may indeed be necessary.

There is also another angle: Nvidia’s bets on OpenAI and Anthropic are not just about selling more GPUs. Both companies are preparing for IPOs in 2026. Once they list and their valuations crystallize, Nvidia, as an early shareholder, stands to capture significant upside from the equity itself.

Cheap on Valuation, but No Buyers: Where Did the Money Go?

On traditional valuation metrics, Nvidia actually looks inexpensive. The stock trades at roughly 20 times 2027 forward earnings, close to the S&P 500’s 22‑times multiple—but Nvidia is still expected to grow EPS at a roughly 35% compound annual rate, with free‑cash‑flow growth above 40%. By comparison, Broadcom—another big beneficiary of AI spending—commands higher multiples on both current and forward earnings.

Sell‑side targets cluster in the 250–275‑dollar range, implying about 26–28 times 2027 earnings. With the shares around 180 dollars, that suggests 30–40% upside on paper. The catch is that cheap does not automatically mean there is incremental demand. New money has increasingly flowed instead into memory makers and foundries, which offer higher operating leverage.

The logic is simple. In 2023–2024, if you wanted AI exposure, the simplest move was to buy Nvidia. By 2026, AI infrastructure investment has climbed to the edge of what existing manufacturing capacity can support. Even if GPU demand keeps growing fast, the earnings torque at the “edges” of the value chain—HBM memory, TSMC’s advanced nodes, packaging and testing equipment—can be higher, because those businesses are smaller and supply is tighter.

This is not about Nvidia’s fundamentals collapsing. It is about a shift in the risk‑reward calculation. When other stocks tied to the same AI narrative offer greater upside elasticity, capital naturally rotates toward them.

AI CapEx Slows in 2026: Why Is Capital Waiting for a Signal?

Another reason investors are hesitant to rotate back into Nvidia is deeper: the growth rate of AI capital expenditures is starting to trend down.

On the surface, Wall Street still looks optimistic about 2026. Bullish forecasts suggest that AI‑related CapEx by the hyperscalers could rise nearly 40% year on year, pushing total spending above 600 billion dollars. That sounds robust. The unease lies in the slope: growth is expected to decelerate from around 70% in 2025 to the low‑30% range in 2026.

If that trend continues, by late 2026 AI CapEx growth could look similar to traditional IT spending. For Nvidia, that would likely mark the end of its extreme hyper‑growth honeymoon phase.

Worse, the internal divergence across the big platforms is widening. Meta is still investing at a 40‑plus‑percent pace, while Amazon and Google are only guiding to low‑teens growth. That split already signals different views on the returns to AI investment. Roughly half of Nvidia’s data‑center revenue comes directly from these hyperscalers, so any tightening or acceleration in their CapEx plans gets magnified in how the market handicaps Nvidia’s order book.

In this context, investors are choosing to wait. It is not that they doubt Nvidia’s earnings power; they want clarity on whether AI CapEx is entering a more moderate, sustainable “new normal” or heading toward a more abrupt brake.

Why Everyone Is Waiting for GTC in March

That is why the market is now fixated on a single “decision point”: Nvidia’s GTC conference in mid‑March 2026.

At that event, Nvidia is expected to give more concrete details on Rubin’s specifications, ramp‑up schedule, and initial anchor customers. Investors are also hoping for another dose of assurance from Jensen Huang: a clearer view of the total addressable AI‑infrastructure opportunity and its pacing, the capital‑spending capacity of Nvidia’s largest customers, and how far Nvidia plans to go in funding its own customer base.

Until then, the stock is likely to trade sideways in a roughly 180–210‑dollar range. To break out of that band, the market probably needs to see three things:

- OpenAI, Oracle, and other key customers making visible progress on fundraising and IPO plans, proving that the ecosystem’s funding chain is intact.

- A credible order pipeline and production‑ramp roadmap for Vera Rubin, strong enough to counterbalance structural pressure from ASICs and in‑house chips.

- A clearer narrative around Nvidia’s equity investments in customers—one that convinces investors this is not just circular financing inflating revenue, but a strategy that can deliver long‑term returns on the equity side as well.

None of these are small asks. They map directly onto three core dimensions: sustainability of demand, strength of the technology moat, and quality of earnings.

So, What Should People Really Be Worried About?

This is the core tension around Nvidia today. Look backward at the last three years, and the company clearly deserves a higher valuation. Look forward to the possibility of AI CapEx slowing after 2026, and the market is understandably reluctant to award more aggressive multiples.

The result is a company that remains central to AI infrastructure at the fundamental level, but in the public markets has already drifted from “must‑own core holding” to just one of several names investors now feel they can pick and choose among. For short‑term capital, that shift in status is deeply uncomfortable. For long‑term investors, though, if you stretch the horizon to three to five years, today’s price level—while not a bargain basement—already looks quite attractive.