What Is the Fed’s Monetary Policy Framework? Does the 2025 Update Mean a More Hawkish or Dovish Fed?

TradingKey - As Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell signaled rate cuts at the 2025 Jackson Hole symposium, the Fed also unveiled a major update to its five-year monetary policy framework review, reflecting the need to adapt to new economic realities.

The 2025 policy framework adjustment re-balances the Fed’s dual mandate of maximum employment and price stability. Compared to the 2020 framework, the 2025 version removes references to the “low inflation, low unemployment, low growth” environment, eliminates the “make-up” inflation strategy, and drops the term “shortage” in describing labor market conditions.

Overall, the new framework marks a shift away from the pandemic-era strategy of tolerating higher inflation to preserve employment, and a return to a flexible inflation targeting regime that prioritizes price stability, reduces tolerance for high inflation, and increases tolerance for low unemployment.

The Evolution of the Fed’s Monetary Policy Framework

Although the Fed’s dual mandate has roots in the 1970s, the formal policy framework is relatively new. The Fed’s framework has evolved in four key stages:

- 1977: Dual mandate established

- 2012: 2% inflation target formalized

- 2020: Flexible Average Inflation Targeting(FAIT) introduced

- 2025: Return to Flexible Inflation Targeting

In February 2012, the Fed published its first "Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy", formally defining its commitment to Congress’ dual mandate of maximum employment and price stability. This statement became the foundation for all future monetary policy decisions, with FOMC members regularly citing it to justify their policy choices.

The Fed committed to reviewing the statement annually, but it wasn’t until 2019 that the first public review took place.

At the August 2020 Jackson Hole symposium, the Fed released an updated framework and announced it would review the framework every five years — a commitment to reassess policy effectiveness in light of structural economic changes.

After the post-pandemic inflation surge, the 2020 framework — designed for a low-rate environment — proved ill-suited for the new economic era. A 2025 update was inevitable.

The 2020 Framework: Employment Priority

Before the 2012 framework, the U.S. economy was characterized by expansion and rising inflation. The Fed believed monetary policy could not sustainably boost employment in the long run, while inflation was seen as a monetary phenomenon — thus, price stability was prioritized.

From 2012 to 2020, the U.S. entered a “triple-low” environment: low inflation, low unemployment, low growth — and the Fed operated under low interest rates.

- Low inflation: From Feb 2012 to Aug 2020 (103 months), median CPI YoY was 1.7%; with 20 months below 1%, 29 months above 2%, none above 3%

- Low unemployment: The U.S. experienced its longest expansion, with unemployment falling to a 50-year low, below the natural rate. CBO’s estimate of natural unemployment dropped from 4.93% (2012) to 4.41% (2020)

- Low growth: Slowing population growth, aging, and weak productivity led to subpar GDP growth — near the lowest since 1950 — with signs of secular stagnation. This also pushed down the neutral interest rate.

U.S. GDP Growth, Source: World Bank

Against this backdrop — and amid the economic uncertainty of the pandemic — the Fed revised its framework in August 2020 to allow for temporary inflation overshoots and to prioritize maximum employment.

Key changes:

- Redefined the 2% inflation target as Flexible Average Inflation Targeting (FAIT) — allowing inflation to run above 2% after prolonged periods below target, increasing tolerance for inflation

- Elevated the priority of maximum employment, shifting focus from “deviations” to “shortfalls” in employment, and no longer treating low unemployment as a trigger for rate hikes

In short, the 2020 framework reflected the need for emergency easing, shifting the policy focus from “price stability first” to “tolerate inflation, prioritize jobs.”

The 2025 Framework: Return to Price Stability Priority

Soon after the 2020 update, U.S. inflation surged to a 40-year high, casting doubt on the framework’s effectiveness.

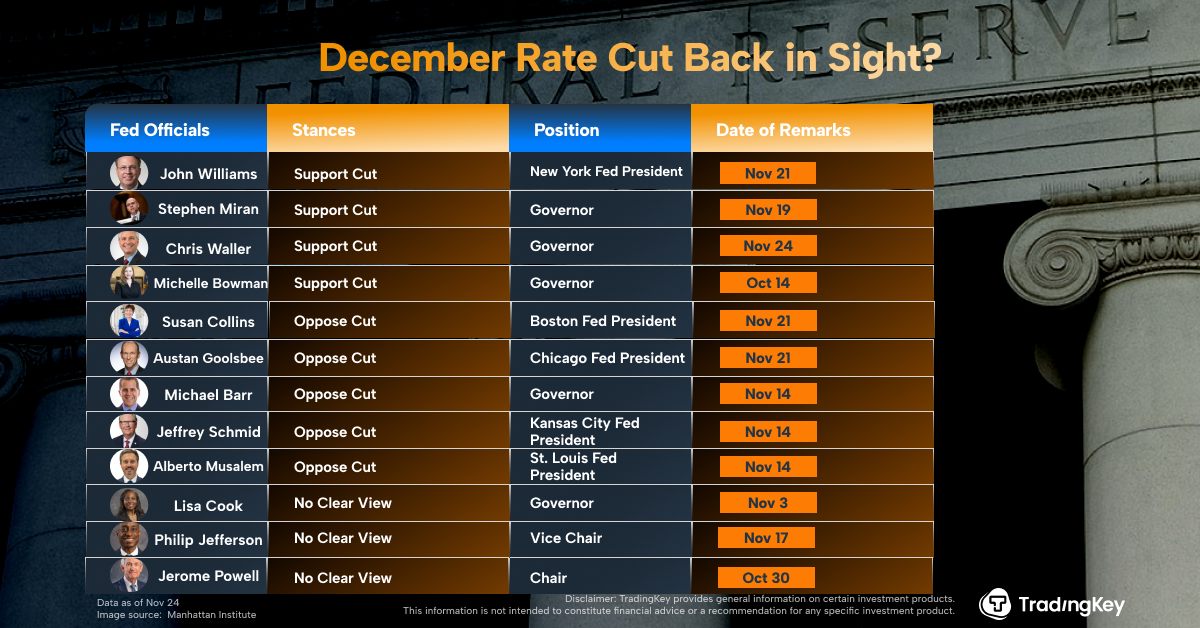

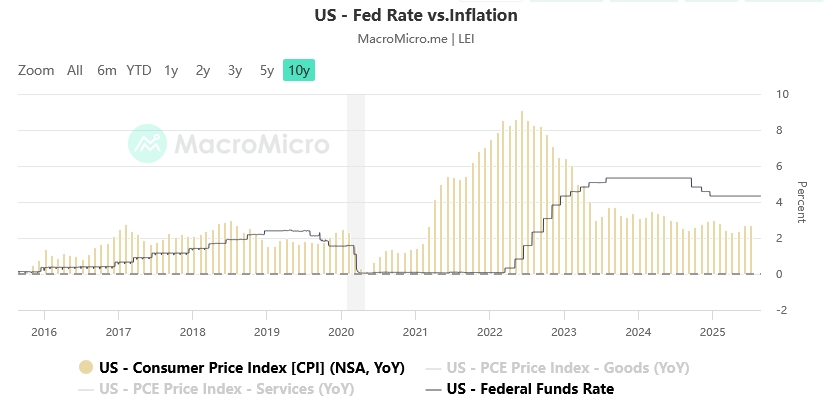

U.S. CPI peaked at 9.1% in June 2022, forcing the Fed to raise rates 11 times in its 2022–2023 hiking cycle — a stark contrast to the anticipated prolonged easing.

U.S. Fed Funds Rate and Inflation, Source: MacroMicro

The U.S. rapidly shifted from a “low inflation, low rates” to a “high inflation, high rates” environment, making a policy overhaul urgent.

According to an Everbright Securities report, the Fed’s policy evolved through three phases from 2020 to early 2025:

- Counter economic pressure, maintain zero rates: Cut rates by 150 bps in March 2020, kept near zero until March 2022

- Fight inflation, but act slowly: Massive fiscal and monetary stimulus fueled demand, while supply constraints caused inflation to spike. Bound by FAIT, the Fed lagged behind inflation — policy rates peaked 13 months after CPI

- Inflation cools, dual goals rebalanced: Rate hikes tamed inflation, and the Fed began a new easing cycle in September 2024, cutting 100 bps in 2024. But in 2025, Trump’s tariffs complicated further cuts, while labor market weakness grew

With Trump back in the White House, the Fed faces new challenges:

- Trump’s anti-globalization policies create long-term inflation uncertainty

- Tighter immigration policies constrain labor supply

- Post-high-rate environment pressures unemployment

- “Fire Powell” and “Fire Cook” moves threaten Fed independence

In May 2025, Powell signaled a major review of the 2020 framework, especially the focus on “shortfalls” and “average inflation targeting.” In August 2025, at Jackson Hole, Powell announced a revised "Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy." The new framework includes three key changes:

1. Remove references to low-rate environment: Delete mentions of the effective lower bound (ELB), acknowledging that higher inflation may push up the neutral rate.

Powell said:

“At the time of the last review, we were living in a new normal, characterized by the proximity of interest rates to the effective lower bound (ELB) along with low growth, low inflation, and a very flat Phillips curve — meaning that inflation was not very responsive to slack in the economy.”

Brookings noted the 2020 framework is outdated — the new risk isn’t too little inflation, but too much.

2. Drop “average” in flexible average inflation targeting: Return to flexible inflation targeting, eliminate the “make-up” strategy, and commit to anchoring long-term inflation expectations — signaling lower tolerance for inflation above 2%.

Powell said:

“As it turned out, the idea of an intentional, moderate inflation overshoot had proved irrelevant. There was nothing intentional or moderate about the inflation that arrived a few months after we announced our 2020 changes to the consensus statement, as I acknowledged publicly in 2021.”

3. Remove “shortage” from labor market description: The 2020 framework replaced “deviations” with “shortfalls,” emphasizing action on labor “slack” but hesitating to hike rates when labor was “tight.”

The new framework states:

“Employment may at times run above real-time assessments of maximum employment without necessarily creating risks to price stability.”

Analysts say this raises the bar for preemptive rate hikes — acknowledging that in a constrained labor market, low unemployment doesn’t necessarily signal inflation risk.

In short, the 2025 framework re-balances employment and inflation, no longer assuming low rates are the norm, and places greater emphasis on price stability and policy flexibility.

More Hawkish or More Dovish?

The framework update is the Fed’s recalibration to new economic conditions. Analysts are divided on its implications for the neutral rate.

Nationwide said the Fed has returned to its pre-pandemic framework — a symmetric approach to inflation and employment — moving past the asymmetric focus on high unemployment and concerns about rates hitting the ELB.

RSM US LLP economists argue the framework could lead to higher rates. By refocusing on price stability and the 2% target, it signals that even with near-term rate cuts, markets should prepare for longer-term tightening.

On tariffs, Powell said the baseline is that tariff effects are temporary, one-time price changes, but uncertainty remains. Tariff impacts take time to ripple through supply chains, and frequent changes could prolong the process.

But David Wilcox, PIIE researcher, disagrees that a return to symmetric targeting implies a more hawkish Fed. He calls the “asymmetric approach” a design flaw and says focusing on actual inflation outcomes is a positive step for anchoring expectations — not a clear signal of hawkishness or dovishness.

David Wessel, Senior Fellow at Brookings, added:

“It did not, despite some urgings from outside the Fed, offer any new insight into the conditions that it believes will warrant deploying what are sometimes called unconventional monetary policy tools—forward guidance and quantitative easing—nor how they might be deployed, nor what lessons it learned from the use of these tools during the pandemic.”

Everbright Securities concluded the new framework reflects adaptation to current conditions but cannot be clearly labeled hawkish or dovish — its impact on long-term rates is neutral.

Compared to Powell’s dovish signal of imminent cuts, New York Fed President John Williams said at the end of August that there’s little evidence the neutral rate has risen significantly from its pre-pandemic low — suggesting the era of low rates is not over.

Commentators note Williams’ statement challenges the “higher-rate” narrative, with Powell focusing on short-term flexibility and Williams on long-term rate paths.

In reality, Fed estimates of the neutral rate remain highly divergent: the median forecast has risen from 2.5% pre-pandemic to 3%, but the range is 2.5% to 4%.