TradingKey - Since the launch of the first ETF, the SPY (S&P 500 Index ETF), in 1993, exchange-traded funds (ETFs) have fundamentally reshaped the global investment landscape. As an innovative tool blending the diversification strengths of mutual funds with the trading flexibility of individual stocks, ETFs have rapidly become a core allocation choice for investors of all types, leveraging their unique attributes.

For retail investors, the value of ETFs is straightforward and practical: with just a few hundred dollars, you can instantly gain exposure to U.S. blue-chip giants like Apple and Microsoft through SPY or VOO (S&P 500 ETFs)—no need to individually screen stocks.

State Street Investment Management disclosed in October that U.S. ETFs have already attracted over $1 trillion in inflows this year. The firm also projects that annual U.S. ETF inflows could set a record of $1.4 trillion by the end of 2025.

But does such intense investor enthusiasm mean ETFs are truly foolproof and flawless? The answer is clearly no. Like all financial products, ETFs carry hidden risks beneath the surface.

Therefore, deeply understanding the essential characteristics, advantages, and limitations of ETFs is not only a prerequisite for determining their fit within a personal investment portfolio but also the key to maximizing returns while controlling risk.

Seven Advantages of ETFs

- Portfolio Diversification

The core value of ETFs lies in building diversified allocations at extremely low thresholds. With a single trade, investors can simultaneously hold dozens to thousands of assets through one ETF—whether cross-border equity portfolios (e.g., global ETFs covering markets across 49 countries), multi-asset combinations (stocks + bonds + commodities), or niche industry themes (clean energy, biotechnology).

This "basket of assets" mechanism fundamentally avoids unsystematic risk from individual securities. When investment portfolios achieve diversification across multiple asset classes, geographic regions, and industry sectors via ETFs, the negative impact of any single stock’s underperformance on overall returns is substantially reduced.

Especially for non-professional investors, ETFs provide a practical solution for efficient diversified investing. By allocating to a single fund, investors indirectly hold stocks of numerous companies. The market offers abundant ETF products specializing in specific stock categories, industry sectors, bond types, and currency classes, enabling investors to achieve portfolio diversification without needing deep expertise in each niche—greatly lowering the professional knowledge barrier.

- Rich Investment Choices

The global ETF market has evolved into a large-scale, continuously expanding product ecosystem where each product’s investment objectives and strategy designs are distinctly differentiated.

Current ETF categories in the market are exceptionally diverse, covering equity-type, bond-type, commodity-type, real estate-type, and hybrid products for multi-asset allocation. In terms of coverage, nearly every mainstream asset class, commodity, and currency has corresponding ETF products providing tracking services. Whether investors seek exposure to popular stock indices, focus on specific bond categories like corporate debt, or hedge against exchange rate fluctuations of major currencies like the U.S. dollar, matching options exist in the market.

Their investment logic and operational methods also show clear differentiation. In investment style, some pursue aggressive high-return strategies while others emphasize conservative value growth. In scope, specialized products deeply focus on single asset classes while comprehensive ETFs adopt cross-domain layouts. Leveraging this diversity, investors can select suitable products based on their risk preferences and goals to build personalized diversified portfolios.

For aggressive investors pursuing specific strategies, leveraged ETFs and inverse ETFs have also become important tools. However, the risks of these two product types are significantly higher than traditional ETFs and are generally unsuitable for long-term holding investors.

(Source: Freepik)

- Round-the-Clock Trading Flexibility

Throughout the trading day, investors can buy and sell ETF shares at current market prices through brokerage accounts. Unlike mutual funds—which are priced only at net asset value (NAV) once daily at market close—ETFs continuously quote prices on secondary markets during trading hours.

Their transaction prices are dynamically determined by real-time supply and demand and may deviate slightly from NAV. This intraday liquidity design, combined with no minimum holding period requirements, empowers investors to instantly respond to market changes and flexibly adjust portfolio allocations.

This feature significantly expands strategic implementation possibilities. Investors can comprehensively utilize leverage mechanisms, inverse positioning strategies, and price-based conditional orders (such as limit orders) to precisely manage volatility risk.

This tactical flexibility enables ETFs to serve both core long-term asset allocation needs and act as instruments for expressing short-term market views, accommodating the full spectrum of investment objectives—from conservative to aggressive.

- Cost Efficiency

The vast majority of ETFs adopt passive management models. Their mainstream products focus on passive tracking strategies with the core objective of precisely replicating benchmark index performance, rather than pursuing excess returns through active market timing or individual stock selection.

This design inherently eliminates high costs associated with actively managed funds—such as large research teams and frequent portfolio rebalancing—resulting in significantly lower management fees for ETFs. More critically, the low turnover characteristic of index-based operations further compresses transaction friction costs: every reduction in unnecessary buy-sell operations directly translates into net returns retained by investors.

While investors still bear bid-ask spreads, leading brokerages have widely introduced $0-commission ETF trading services, driving comprehensive holding costs to continuously decline.

Typically, the average cost of investing in a single ETF is substantially lower than directly purchasing all underlying stocks covered by that ETF. Upon buying an ETF, investors automatically gain proportional ownership of all fund holdings. Similarly, selling an ETF requires only one transaction. Reducing trade frequency significantly saves brokerage commissions, and selecting brokers offering low- or $0-commission ETF trading can further reduce costs.

- High Liquidity

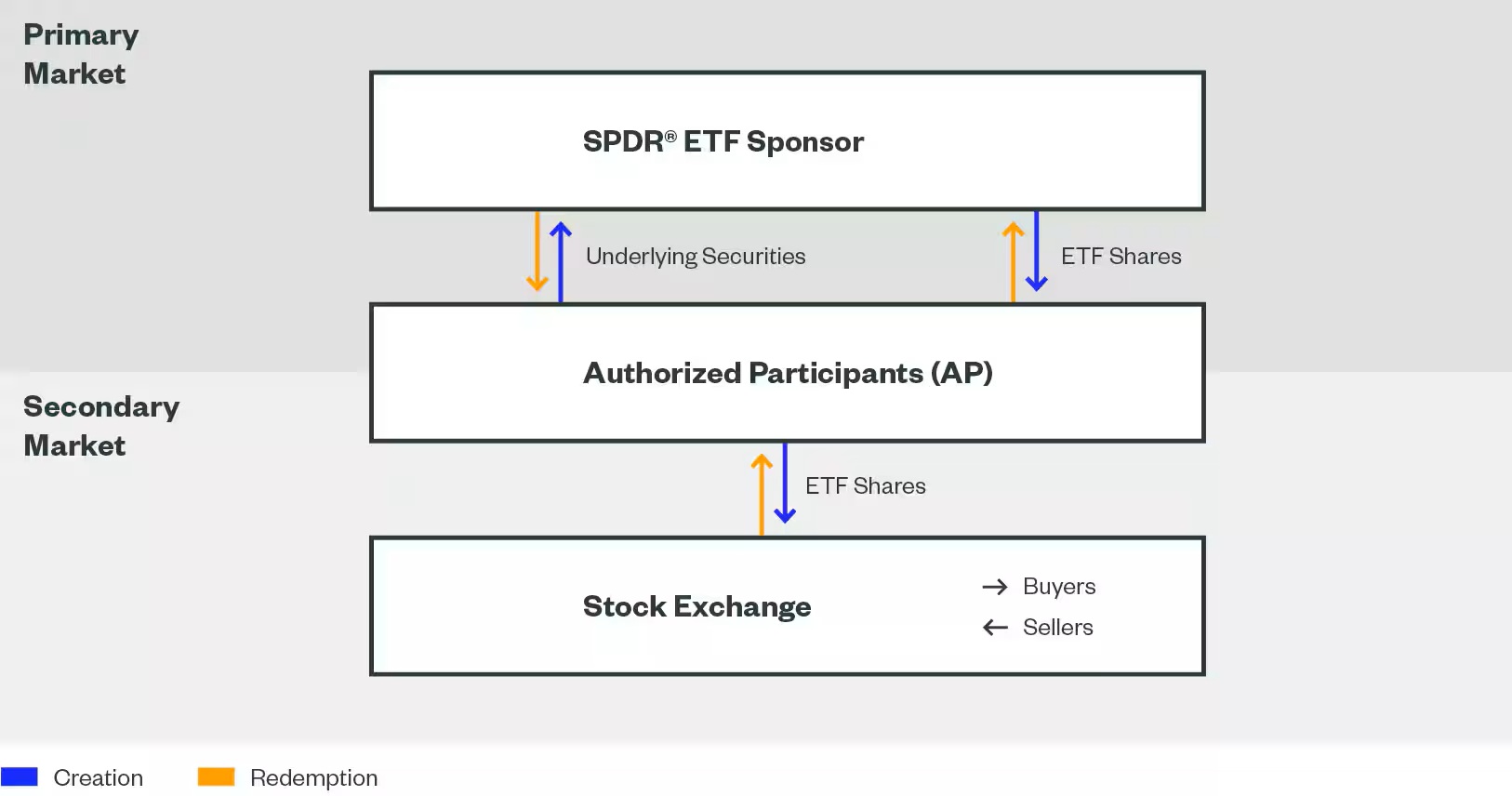

The value of liquidity becomes especially prominent during market volatility. All investors desire the ability to buy and sell securities quickly, conveniently, and at low cost. ETFs’ uniqueness lies in deriving liquidity from dual-market support.

In the secondary market where most investors participate, ETF liquidity is provided by real-time trading on exchanges. ETFs trade continuously throughout the day on secondary markets, enabling investors to make timely decisions and execute trades based on live market conditions—without waiting for specific settlement windows.

Secondary market liquidity fundamentally relies on the liquidity of the ETF’s underlying securities in the primary market—in some cases, primary market liquidity even exceeds secondary market depth.

(Source: State Street Investment Management)

Like individual stocks, ETFs are listed on securities exchanges and can be traded anytime during the entire trading day. This trading flexibility further enhances liquidity, allowing investors to rapidly respond to market volatility. During volatile periods, the ability to quickly establish or close positions helps protect capital while timely capturing potential growth opportunities.

- High Transparency

Most ETFs offer exceptionally high portfolio transparency with mandatory daily disclosure mechanisms. This routine information openness enables investors to monitor their allocation positions in real time, providing strong support for making wiser, more precise investment decisions.

Compared to many mutual funds, ETFs maintain higher disclosure standards, with transparency being a particularly prominent advantage. Especially for index-tracking ETFs, complete portfolio holdings are publicly disclosed daily, allowing investors to clearly understand exactly which assets their capital is allocated to.

For investors, clear capital flow directions equate to decision-making confidence. By understanding an ETF’s underlying holdings, investors can more accurately determine whether the product aligns with their personal investment needs, thereby precisely identifying suitable investment tools.

- Tax Efficiency

Tax optimization capability is one of the core strengths of ETFs, particularly helping investors in taxable accounts retain more of their actual returns.

ETFs’ tax advantages primarily stem from two aspects:

First, most ETFs operate with passive index-tracking structures that generally exhibit low turnover rates. Fewer portfolio adjustments mean fewer asset sales, naturally reducing the frequency of capital gains realization—and consequently lowering capital gains tax liabilities for investors.

Second, ETFs’ unique product structure typically delivers superior tax efficiency compared to mutual funds or investment trusts: in many countries and regions, investors pay capital gains taxes only when they actively sell ETF shares. In contrast, mutual funds or investment trusts may trigger taxable events annually for investors due to internal transactions by fund managers or dividend distributions—even without the investor selling their holdings.

Five Disadvantages of ETFs

- Market Risk

Market risk is the primary risk faced by ETF investors, fundamentally stemming from the strong correlation between ETFs and their underlying benchmarks—an ETF’s value fluctuates directly with the performance of the market, sector, or index it tracks.

If the broad index, specific industry segment (such as technology or energy), or niche theme tracked by an ETF declines due to macroeconomic downturns, industry policy adjustments, or depressed market sentiment, the ETF’s net asset value and trading price will shrink correspondingly.

Additionally, during periods of severe market turbulence or temporary liquidity constraints, an ETF’s secondary market trading price may deviate significantly from its net asset value (NAV). This price-NAV misalignment reduces trading efficiency and adversely impacts both buyers and sellers.

Specifically, if an ETF trades at a substantial premium to its NAV (trading above intrinsic value), buyers may overpay for the underlying assets. Conversely, if it trades at a discount (below NAV), sellers may incur losses from undervalued asset realization.

- Limited Diversification

Many ETFs—particularly those focused on single sectors or specific themes—often fail to achieve broad diversification, instead concentrating heavily on a limited number of core holdings within that domain. Should the corresponding industry or theme enter a downturn (due to policy adjustments, demand contraction, etc.), this concentrated positioning significantly amplifies loss exposure.

Some indices inherently cover a narrow range of stocks, potentially focusing exclusively on specific sectors, overseas markets, or large-cap stocks while lacking exposure to small- and mid-cap companies. These structural gaps cause portfolios to skew toward a single dimension, potentially missing growth cycles in smaller firms and failing to hedge volatility risks through diversified holdings.

Furthermore, despite continuous expansion of the ETF universe, product availability for specialized needs remains limited compared to traditional tools like mutual funds. For instance, customized offerings targeting specific investment styles, niche sectors, or precise risk tiers are scarce. This may prevent investors from finding ETFs perfectly aligned with their objectives and risk profiles, ultimately undermining portfolio diversification effectiveness.

(Source: Freepik)

- High Short-Term Trading Costs

While ETFs’ continuous intraday trading appeals to short-term traders, the cumulative cost of frequent transactions cannot be ignored—brokerage commissions from each trade progressively erode actual investment returns.

Although passively managed ETFs typically carry low annual expense ratios, this does not eliminate transaction costs. For investors employing regular purchase strategies (such as dollar-cost averaging) or executing small, frequent trades, accumulated commissions can offset the advantages of low management fees, driving total costs upward.

Not all ETFs follow passive management. Actively managed ETFs, overseen by portfolio managers aiming to outperform the market, generally charge higher fees to cover professional teams conducting security selection and strategic adjustments. If an active ETF underperforms, these elevated long-term fees may directly erase existing gains.

- Tracking Error Exists

Tracking error reflects the deviation between an ETF’s actual performance and its benchmark index’s returns, focusing primarily on the long-term stability of this deviation rather than absolute return levels.

For index-oriented investors seeking precise benchmark replication, tracking error is undeniably critical. Elevated tracking error not only increases return uncertainty but may also generate hidden costs that hinder the achievement of investment objectives.

While low fees are a core advantage of ETFs, significant tracking error can offset these cost savings. Therefore, when evaluating long-term performance—especially in fixed income ETFs where tracking error tends to be more pronounced—assessing both expense ratios and tracking error simultaneously becomes particularly crucial.

- Limited Investment Control

When investing in ETFs, investors purchase a predefined basket of assets whose selection logic is entirely driven by the fund’s core objectives.

In practice, a fund’s primary investment focus may not fully align with an individual’s preferences—for example, some ETFs may include sectors an investor disapproves of or companies involved in ethical controversies. In such cases, investors have minimal ability to adjust ETF holdings, far less than the autonomy afforded when directly selecting individual stocks or bonds.

Choosing Whether to Invest in ETFs

Whether investors should include ETFs in their portfolios is not a binary decision—it requires comprehensive evaluation based on personal investment goals, asset preferences, risk tolerance, and other factors. An ETF’s suitability fundamentally depends on how well its characteristics match the investor’s needs.

When investors seek more flexible trading experiences than traditional mutual funds offer, ETFs are often appropriate—their ability to execute real-time orders during market hours and generate instant trade confirmations satisfies demands for immediate decision-making.

For investors prioritizing cost-efficient diversification, ETFs similarly shine. With a single transaction, funds can be allocated across diverse assets spanning companies, industries, currencies, and countries—eliminating the need to individually screen stocks or bonds and substantially lowering portfolio construction barriers and costs.

However, for investors who value autonomous control over underlying holdings, ETFs may not be optimal. Such investors typically prefer personally selecting assets aligned with their values—a need that ETFs’ preset portfolios cannot fulfill. In these cases, direct investment in individual stocks better aligns with their requirements.

Core Preparation Before Investing: Five Key Dimensions for ETF Selection

Regardless of investment needs, investors must conduct systematic due diligence before purchasing an ETF to avoid decision bias caused by information gaps. Core research should focus on the following five dimensions:

- Alignment of Strategy and Objectives

Investors must first confirm whether the ETF’s investment strategy aligns with their financial goals—is it seeking broad market exposure, targeting growth opportunities in specific sectors, or prioritizing stable income? ETFs with different strategies serve distinctly different use cases.

- Diversification Awareness

Investors should review the ETF’s holdings composition to verify whether its covered asset classes (e.g., large-cap stocks, bonds, international assets) match their allocation plan. Crucially, they must guard against excessive concentration risks in single securities, sectors, or geographic regions to ensure effective risk diversification.

- Reasonable Cost Structure

Management fees significantly impact long-term returns. Investors should benchmark the target ETF’s expense ratio against peer products to assess whether the fee aligns with the asset exposure and management services provided, avoiding erosion of long-term gains by excessive costs.

- Product and Provider Reliability

Prioritize ETFs issued by reputable, operationally stable institutions with mature governance frameworks and stronger risk controls. Simultaneously, confirm that the index tracked by the ETF has high market recognition and replicability—avoiding unexpected tracking deviations caused by poorly constructed indices or excessively volatile underlying assets.

- Liquidity Assurance

Investors must evaluate the ETF’s average daily trading volume and bid-ask spread to ensure efficient trade execution when needed. Products with small scale or low trading activity may face liquidity risks, causing actual transaction prices to deviate significantly from net asset value.