TradingKey - Matthew, 36, has just handed in his resignation. While he’s excited about new opportunities, he also feels a hint of anxiety about the unknown. As he packs up his desk, he realizes there’s one crucial matter—beyond wrapping up projects, updating his résumé, and planning his next career move—that will impact his financial security for decades to come: his 401(k) account.

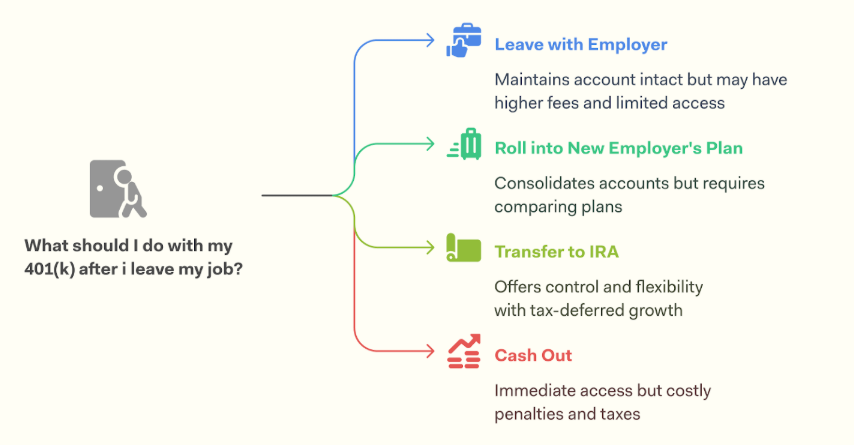

After all, the retirement savings he and his former employer have contributed over the past ten years won’t automatically “follow him.” The money won’t disappear, but it also won’t make the best decision on its own. Matthew needs to take action and decide what to do next: leave it in the old plan, roll it into his new employer’s plan, transfer it to an IRA, or… (he’s heard some people just cash it out—but that seems extremely costly).

Matthew’s situation is familiar to many professionals. If you’ve ever changed jobs, you’ve likely asked yourself the same question: What should I do with my 401(k)?

Below, we’ll clearly break down these four common options and their ideal use cases, helping you choose the smartest path based on your personal circumstances.

(Source: Farther)

What Should You Consider When Rolling Over a 401(k)?

Before making any decisions about your 401(k) account, there are several key factors you must clarify in advance to avoid unnecessary tax liabilities or financial losses down the road.

Vesting Status

Your own salary-deferral contributions to your 401(k) always belong to you, but employer matching contributions are typically subject to a vesting schedule.

If you leave your job before becoming fully vested, any unvested portion of the employer match will be forfeited back to the company.

Therefore, be sure to log in to your 401(k) plan portal to confirm your vested balance—this is the actual amount you can take with you.

Outstanding Loan

If you’ve borrowed from your 401(k), leaving your job triggers an accelerated repayment clause. You’ll typically have a limited window—usually 60 to 90 days—to repay the outstanding loan balance in full.

If you fail to repay on time, the unpaid amount will be treated as an “early distribution,” subject to ordinary income tax plus a 10% penalty if you’re under age 59½.

As many retirement planning experts repeatedly emphasize, a 401(k) loan may seem harmless while you’re employed, but once you leave your job, it can quickly turn from a convenient tool into a financial time bomb.

So assess your ability to repay the loan in advance. If you can’t repay it all at once, consider using other funds to cover the balance or pay off the loan before your departure date.

Account Balance

Your account balance directly affects what your former employer is allowed to do with your account:

- Below $1,000: Your former employer may issue you a check (typically with 20% federal tax withheld) or automatically roll the funds into an IRA.

- $1,000–$7,000: If you don’t proactively roll over the funds yourself, your former employer may automatically transfer the balance into an IRA (known as a “mandatory distribution”).

- Above $7,000: You generally have full control—you can leave it, roll it over, or cash out. You may keep the account with your former employer indefinitely; the employer cannot force you to remove it.

Option 1: Leave Your 401(k) with Former Employer

If your account balance exceeds $7,000, most 401(k) plans allow you to keep your funds in the former employer’s plan. This option can be advantageous in certain situations.

The old plan might offer better investment choices or lower fees than your new employer’s plan. More importantly, if you leave your job in the year you turn 55 or later, you can take penalty-free withdrawals from that specific 401(k) account (the “Rule of 55”).

Additionally, 401(k) accounts generally offer stronger legal protection against lawsuits or bankruptcy than IRAs.

For investors holding company stock in their 401(k), there’s also the opportunity to use the Net Unrealized Appreciation (NUA) strategy. By distributing the stock directly to a taxable brokerage account, you pay ordinary income tax only on the original cost basis. In contrast, future gains are taxed at the lower long-term capital gains rate, potentially resulting in significant tax savings.

Another benefit: if you’re still working past age 72, you’re not required to take Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) from your current employer’s 401(k).

However, there are drawbacks.

Keeping an old account means you can no longer make contributions, investment options may be inflexible, and if your holdings overlap with those in your new employer’s retirement plan, it could lead to overconcentration in certain asset classes, increasing risk.

A more practical concern is forgetfulness—as career changes become more frequent, many people leave old accounts untouched for years.

If your former company undergoes a merger or even bankruptcy, the funds remain protected, but the transfer process can become extremely cumbersome due to complex administrative approvals. Therefore, if you choose to keep the account, be sure to stay engaged—update your contact information, monitor account activity, and regularly review whether the investment allocation still aligns with your retirement goals.

Option 2: Roll Over to Your New Employer’s 401(k) Plan

Transferring your funds into your new employer’s plan helps simplify account management and consolidate your retirement assets. However, this is only possible if the new plan accepts incoming rollovers—and traditional and Roth balances must be rolled into their respective account types; they cannot be mixed.

When executing the transfer, always opt for a “trustee-to-trustee” direct rollover—where the funds move directly from your old plan administrator to the new plan, without passing through your hands. This avoids the mandatory 20% federal tax withholding and eliminates the pressure of the 60-day deadline to redeposit the funds.

If a check is issued to you personally, you’ll need to use your own money to cover the withheld 20% and deposit the full amount into the new account within 60 days. Otherwise, the missing portion will be treated as a taxable distribution and may incur penalties.

Additionally, some new employer plans impose a waiting period of 30 to 90 days before accepting rollovers, so confirm the timeline in advance. When done correctly, a direct rollover is entirely tax-free—but mismatched account types or procedural errors could trigger unintended taxable events.

Option 3: Roll Over to an Individual Retirement Account (IRA)

For investors seeking greater flexibility, rolling over to an IRA is often a highly attractive choice. An IRA is a personal tax-deferred account that offers a convenient way to save for retirement.

IRAs typically provide a much broader selection of funds, ETFs, and even individual stocks than most 401(k) plans, with more transparent fee structures. They also support more sophisticated estate planning and Required Minimum Distribution (RMD) management—for example, allowing you to aggregate RMDs from multiple IRAs for calculation purposes.

In 2025, the annual IRA contribution limit is $7,000 ($8,000 for those aged 50 and older)—lower than 401(k) limits, but still valuable as a supplementary retirement account.

As long as the rollover is completed via a direct trustee-to-trustee transfer, the entire process is completely tax-free and not subject to the 20% mandatory withholding. This option is especially appealing if you’re between jobs, unemployed, or dissatisfied with your former employer’s investment choices—offering a more autonomous alternative.

However, moving to an IRA means permanently giving up access to your former employer’s matching contributions. Additionally, some IRA platforms may charge account maintenance fees, trading commissions, or advisory fees, so you’ll need to weigh flexibility against potential costs.

Option 4: Cash Out

This can be an expensive choice—and therefore, taking a cash distribution is generally considered a last resort.

Unless you qualify for specific exceptions—such as leaving your job in the year you turn 55 or later (and taking the distribution in that same year), incurring medical expenses exceeding 7.5% of your adjusted gross income, or using the funds for a first-time home purchase (lifetime limit of $10,000)—any withdrawal before age 59½ will trigger both income tax and a 10% early withdrawal penalty.

Yet a 2020 study by Alight found that nearly 40% of employees who left their jobs between 2008 and 2017 chose to cash out their accounts, with higher cash-out rates among small balances (under $5,000).

Rationally, you likely understand that tapping retirement savings to cover current expenses often comes at the cost of future financial freedom. But under emotional stress or short-term pressure, people still make decisions they later regret.

(Source: Shutterstock)

When Should You Handle Your 401(k)?

After leaving your job, you don’t need to decide immediately what to do with your 401(k)—but you shouldn’t put it off indefinitely either.

There are two critical deadlines to keep in mind: the 60-day rule and the loan repayment deadline.

If you receive a distribution (for example, a check made out to you), you have 60 days from the date of receipt to roll the full amount into an IRA or a new employer’s qualified retirement plan to avoid tax penalties.

Miss this window, and the entire amount will be treated as taxable income. If you’re under age 59½, you’ll also face an additional 10% early withdrawal penalty—potentially eroding a significant portion of your hard-earned savings.

Additionally, if you still have an outstanding 401(k) loan, your departure typically triggers an accelerated repayment clause.

For these reasons, it’s best to act as early as possible.

On your last day of employment, we recommend completing a few key preparations: gather login credentials for your retirement account, contact information for the plan administrator, and your most recent vested balance (i.e., the portion you truly own, including vested employer matches). Also, request a separation packet from HR—many companies provide a checklist that includes account details, rollover instructions, and important deadlines.

Conclusion

How you handle your 401(k), 403(b), or other workplace retirement account should be based on your overall financial goals, investment preferences, and tax situation.

Take time to carefully compare the fee structures, investment options, and rules of your old and new plans, and thoughtfully weigh the pros and cons of the four main options.

Only by fully understanding the long-term implications of each choice can you make a decision that truly fits your needs—ensuring your retirement savings not only survive a career transition intact, but continue to grow steadily, laying a solid foundation for your future financial freedom.