AMD Q4 Earnings Preview: A Script This Perfect – Can the Stock Still Top It?

AMD's Q4 earnings are expected to be strong, driven by diversified growth across segments. However, a popular thesis that rising memory prices will benefit AMD is flawed, as it pressures PC OEM purchases. The company's AI future hinges significantly on a single customer's deployment schedule for its MI450 GPUs. While core businesses show robust performance, the AI segment faces concentration risk and competition, with a need for broader customer adoption and ecosystem development to justify its current valuation.

AMD (Advanced Micro Devices) is set to report its fourth‑quarter 2025 earnings on February 3, and current market expectations are decidedly optimistic: strong revenue growth, rising profitability, and a data‑center business that’s carrying a lot of investor hopes. But if you break this rosy script down even a little, one part of the logic looks surprisingly counterintuitive: the popular idea that “memory price inflation will help AMD” may not be nearly as attractive as it sounds, and the company’s entire AI future is now effectively riding on a single customer’s deployment timetable.

Let’s walk through what’s really happening, starting with what the market is currently pricing in.

The Q4 Numbers: What to Expect

Metric | AMD Guidance | Consensus Estimate | YoY Growth |

Revenue | $9.6B (±$300M) | $9.67B | +26% |

Adjusted EPS | — | $1.31–$1.33 | +21–22% |

Gross Margin (Non-GAAP) | 54.5% | 54.5% | Flat |

Sources: Zacks

What distinguishes Q4 isn’t just the level of growth, but where it’s coming from. AMD is seeing momentum across all major segments—data center, client/gaming, and embedded—marking genuine portfolio diversification instead of relying on a single engine.

The company has guided for strong double‑digit sequential growth in data center, driven by EPYC server CPUs and MI350 GPUs; continued growth in client; and a return to sequential growth in embedded.

The Memory Price Paradox: When Bullish Catalysts Actually Hurt

You’ve probably seen this thesis making the rounds: DRAM prices surged roughly 300% between mid‑2025 and year‑end, so system prices are rising and premium CPU vendors like AMD will see higher revenue per box.

That logic is mostly wrong.

When a 64GB DDR5 kit jumps from $200 to $900 in three months, PC OEMs don’t accelerate purchases—they slam the brakes. Once memory jumps from 10–12% of system cost to 15–20% and is still rising 50–60% per quarter, the rational move is to defer purchases and wait for stability.

The core driver is high‑bandwidth memory (HBM) for AI accelerators. Every wafer that Samsung, SK Hynix and Micron divert to HBM3/3E and server DRAM for Nvidia and AMD GPUs is capacity that doesn’t go to standard DDR4/DDR5 for PCs. TrendForce’s January 2026 report projected another ~60% surge in server DRAM prices in Q1 2026, with PC DDR4 prices rising as much as 50%.

Dell and Lenovo have announced 15–20% PC price hikes for early 2026. Consumers aren’t simply swallowing those increases. Instead, OEMs are quietly cutting RAM configs—shipping 16GB instead of 32GB at similar price points—while retailers impose limits on standalone memory purchases or bundle RAM with motherboards to move inventory. The post‑pandemic PC refresh already came off its peak; layering a DRAM squeeze on top is a genuine headwind, not a tailwind.

Here’s the ironic twist: AI accelerators themselves are a major driver of this shortage—and AMD’s own MI350 and upcoming MI450 are very much part of that. The MI350 packs 288GB of HBM3E per GPU, a capacity hog that soaks up cutting‑edge DRAM supply. The faster AMD ramps AI accelerators, the tighter standard DRAM supply becomes, which in turn weighs on unit volumes in the very client segment that just printed record revenue.

Q4 2025 likely dodges most of this: the Ryzen 7 9800X3D launched in November and pulled forward a wave of high‑end demand before DRAM prices and supply tightness fully hit the retail channel. But in Q1 and Q2 2026, once that early adopter wave is digested and the full impact of DRAM inflation shows up in street prices, memory becomes a real volume headwind.

So when you hear “rising memory prices” cited as a bull case for AMD, especially for its PC and client business, it’s worth recognizing that the causality is largely reversed.

The Core Business Story: This Part Is Actually Impressive

Before dissecting the AI gamble, it’s worth recognizing what AMD has clearly executed on across its core businesses.

AMD Segment Performance: 2025 Quarterly Progression

Segment | Q1 2025 (YoY) | Q2 2025 (YoY) | Q3 2025 (YoY) |

Data Center | $3.67B (+57%) | $3.24B (+14%) | $4.34B (+22%) |

Client & Gaming | $2.94B (+28%) | $3.62B (+69%) | $4.05B (+73%) |

Embedded | $0.82B (-2.7%) | $0.82B (-4.3%) | $0.86B (-7.6%) |

Total Revenue | $7.44B (+36%) | $7.69B (+32%) | $9.25B (+36%) |

Source: AMD quarterly reports

Two things stand out:

- Data center is now AMD’s largest single segment by revenue and is still growing >20% YoY off a high base.

- Client & gaming snapped back even faster in 2025, with Q3 revenue up more than 70% YoY—EPYC and Ryzen together now carry both scale and growth.

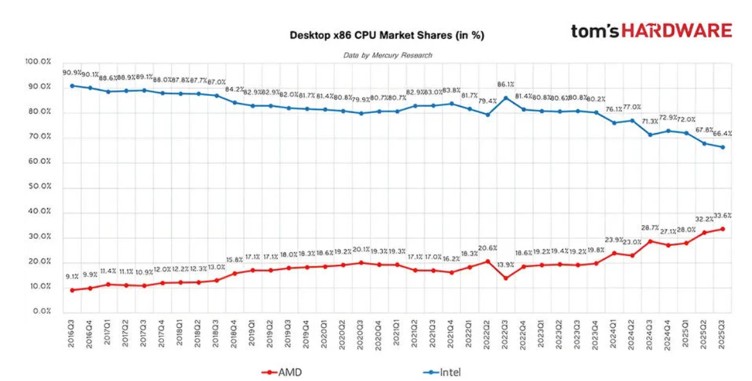

On the server side, Mercury Research data shows AMD’s server CPU unit share around 28% in Q3 2025, but revenue share approaching 40%. In other words, AMD still ships under a third of units, but captures close to four‑tenths of revenue—signaling that it’s winning the higher‑ASP, higher‑margin slices of the market.

That reflects EPYC’s underlying advantage. Fifth‑generation EPYC (“Turin”) delivers roughly 17% higher per‑core performance versus the prior generation and about 37% better per‑core performance on AI and HPC workloads. Versus Intel’s latest Xeon, EPYC can deliver on the order of 30–40% higher throughput in many general compute workloads, about 60% better performance per watt, and materially lower thermal design power—while supporting up to 192 cores per socket versus Intel’s typical 128.

In practical dual‑socket deployments, comparable EPYC systems often deliver 30–40% more compute than Xeon configurations. AMD also offers 12 DDR5 memory channels per socket versus Intel’s 8, translating into up to ~50% higher peak memory bandwidth—a critical edge for memory‑bound workloads like databases, analytics, and in‑memory computing.

On the consumer side, Mercury Research’s Q3 2025 data shows AMD reaching 33.6% desktop CPU unit share—a new all‑time high. In Q4, Ryzen 7 9800X3D became the top‑selling CPU at major retailers within weeks of launch, and during the holiday window AMD’s desktop CPU share at channels like Amazon and Newegg temporarily exceeded 70%. Early 9800X3D batches sold out on arrival at many e‑tailers, supply remained tight, and street prices ran above MSRP. Lisa Su publicly described Q4 as “one of our strongest desktop sell‑through quarters in many years”.

Source: Tom’s Hardware

AI Concentration Risk: One Customer, Tens of Billions at Stake, Almost No Room for Error

Now to the part the market is really paying for—AI.

In late 2025, AMD announced a multi‑year supply agreement with OpenAI to deliver 6 gigawatts of Instinct MI450 GPU compute capacity, the largest single‑customer commitment in the company’s history. AMD has described this as a tens‑of‑billions‑of‑dollars multi‑year revenue opportunity. AMD also granted OpenAI up to 160 million warrants, with vesting tied to GPU deployment milestones and share‑price targets.

OpenAI’s order is real, and the underlying business use cases are very solid: both today’s ChatGPT and tomorrow’s mass‑market intelligent agent systems will require enormous amounts of inference compute to run. But precisely because of that, AMD’s elevated valuation has already priced a large part of this AI growth curve into the stock.

The issue is not whether the demand exists in principle—it’s timing and concentration.

AMD MI450 Deployment Timeline

Milestone | Target Date | Volume | Status |

Initial 1GW deployment start | H2 2026 | 1 GW | Planned; first key milestone in deal |

Remaining ramp | 2027–2028 | 5 GW | Multi-year ramp, dependent on demand |

Total commitment | 2026–2028+ | 6 GW | Multi-year, multi generation framework |

Sources: AMD, OpenAI, Futurum Group, HyperFrame Research

On paper, everything looks like it’s progressing as planned. The uncomfortable question is: who else is buying?

As of early February 2026, OpenAI is still the only customer that has publicly committed to MI450 and Helios at true hyperscale. Oracle has announced plans to deploy roughly 50,000 MI450 GPUs starting in 2026, but relative to a 6GW OpenAI framework, that’s a rounding error. Meta and character.ai have confirmed production deployments of the current‑generation MI350 series, but none has publicly committed to MI450 purchase volumes that would meaningfully diversify the customer base.

That matters because Nvidia hasn’t been idle. After AMD announced the OpenAI deal, Nvidia rolled out its Rubin rack‑scale architecture, offering higher low‑precision compute density per rack than Helios and tying it to a far more mature software ecosystem. Third‑party analyses suggest a fully configured Helios rack can be roughly 20‑something percent cheaper and somewhat more power‑efficient than an equivalent Rubin NVL setup—but those cost advantages only matter if customers are willing to shoulder integration and ecosystem risk.

The CUDA Moat: When Hardware Isn’t the Limiting Factor

Metric | NVIDIA CUDA | AMD ROCm | Gap |

Ecosystem maturity | ~18+ years | ~5 years of heavy investment | Significant |

Developer base | 4M+ registered developers | Order of magnitude smaller (≤100k range) | Tens of x |

Performance | Baseline for most benchmarks | Often ~10–30% slower; worse in some cases | Material |

Framework support | Deep native optimization | Supports major frameworks; many 3P libs still CUDA first | Narrowing but real |

Enterprise share | ~90% of AI accelerator infra | Low single digit share; double digit is a long term goal | Early stage |

Sources: NVIDIA/AMD disclosures, third‑party benchmarks, industry research

Recent benchmarks show that on equivalent‑generation hardware, running the same workload under CUDA versus ROCm can produce performance gaps ranging from about 30% to nearly 2x, a disparity that becomes especially pronounced in large‑scale LLM inference and multi‑node, multi‑GPU environments. For hyperscale cloud providers investing tens of billions of dollars in AI infrastructure, this software‑amplified performance difference is clearly a critical factor in pricing and platform selection.

AMD plans to grow the ROCm developer ecosystem to more than 100,000 people by 2026 and aims to lift its data center AI chip market share into the double digits over the next three to five years. Management expects data center AI revenue to grow at an annualized rate of over 80% during that period. But all of these goals rest on a single premise: AMD needs a much broader customer base and cannot rely on OpenAI as its dominant buyer indefinitely. If OpenAI’s deployment schedule slips by even two quarters, or if issues arise around power delivery, cooling, or software maturity, AMD’s entire AI revenue trajectory will get pushed back. With the stock trading at a forward P/E north of 40x, that’s a setup where the balance between risk and reward is clearly asymmetric.

AMD vs. NVIDIA: Key Metrics

Metric | AMD | NVIDIA | Difference |

Forward P/E | 40–45x | 25–35x | AMD trades at a clearly higher multiple |

Market capitalization | ≈$400B | ≈$4.6T | AMD is roughly 11x smaller |

Quarterly data center revenue | $4.3B (Q3 2025) | ≈$51B (Q3 2025) | About 12x smaller |

Gross margin (non GAAP) | 54% | 75% | 21 percentage points lower |

AI accelerator market share | <10% | 90–92% currently | An 8–10x gap |

Sources: AMD and NVIDIA financials; StockAnalysis; Counterpoint Research

AMD’s current forward P/E of roughly 40–45x represents a substantial premium to NVIDIA’s 25–35x range. That premium exists largely because the market has already priced into the stock a narrative of steadily diversifying AI customers and rising data center profitability—assumptions that are still in the process of being validated.

More subtly, even at this valuation—which has clearly front‑loaded a lot of AI optimism—AMD’s current earnings quality is somewhat stretched. Gross margins look calm on the surface, but in reality they are already operating near the upper bound of the company’s medium‑term target range.

AMD Margin Trends: 2025

Quarter | GAAP Gross Margin | Non GAAP Gross Margin | Non GAAP Operating Margin |

Q1 2025 | 50% | 54% | 24% |

Q2 2025 | 40%* | 43%* (≈54% adj.**) | 12%* |

Q3 2025 | 52% | 54% | 24% |

Q4 2025 (guide) | — | 54.5% | — |

* Includes ~$800M MI308 China export‑control inventory charge

** Adjusted to exclude one‑time inventory charge

Source: AMD earnings reports

Across 2025, AMD grew revenue more than 30%, yet non‑GAAP gross margin sat essentially pinned around 54%. For a company ramping AI GPUs and taking server CPU share, you’d normally expect some visible margin expansion—not a flat line.

Three main factors are at work:

- Product mix isn’t as rosy as it looks. Sell‑side and independent teardown models generally put mature EPYC CPU gross margins in the roughly 50–55% range, while early‑ramp MI3xx GPUs, despite premium positioning, are more likely in the mid‑ to high‑40s due to supply‑chain and yield inefficiencies. The more MI350 you sell at this stage, the more it drags on blended gross margin.

- Operating expenses are growing faster than revenue. In Q3 2025, AMD posted $9.25B in revenue and $2.8B in operating expenses, for a 24% non‑GAAP operating margin—slightly down from 25% in Q3 2024 despite 36% revenue growth. The gap is going into R&D and platform spend: MI450’s software stack, Helios rack‑level integration, and the next EPYC generation are all consuming serious budget.

- Margin expansion is a medium‑term aspiration, not a 2026 base case. At its 2025 Financial Analyst Day, AMD laid out a medium‑term model of 35%+ non‑GAAP operating margin and gross margins trending toward 55–58%. Those targets are achievable in scenarios where AI GPU revenue scales beyond $10B annually at 50%+ margins and EPYC server CPU share stabilizes around the 40% mark. They are much harder to hit on a 2026 timeline if OpenAI remains the only hyperscale MI450 customer and the ramp experiences delays.

What really matters in the Q4 print?

The Q4 numbers themselves will most likely look solid: AMD is quite likely to modestly beat revenue expectations, and management will again emphasize strong data center growth.

Right now, the market’s base‑case for AMD in 2026 is total revenue in roughly the $44–45 billion range, with optimistic “China normalization” scenarios pushing the upper bound toward $50 billion. Within that, AI‑related business (primarily data center GPUs and platforms) is already being modeled at an annualized run‑rate north of $12 billion, and the consensus for 2026 EPS sits around $6–6.5, versus roughly $4 for 2025—implying about 50–60% growth. On paper, that trajectory is enough to support today’s valuation premium—provided execution largely follows the script.

Wall Street’s average price target for AMD currently clusters around $270–280, versus a share price in the 240s, implying roughly 15% upside from here.

The issue is that over the last several quarters, even when AMD has beaten on revenue and EPS, the stock has often traded lower on earnings day—Q2 and Q3 both saw “good numbers, weak price action.” Options pricing going into this report implies roughly a ±9% move around earnings—about ±$22 per share—suggesting that the market is simultaneously bracing for both “good news already priced in” and an amplified volatility response once the results hit.

The Six Questions That Will Actually Move the Stock

Question | Why It Matters | Bullish Signal | Bearish Signal |

1. Helios customer pipeline | Today, only OpenAI is committed at true hyperscale | New hyperscale Helios/MI450 customers named, with scale and timing | Total silence, or vague “in discussions” comments |

2. MI450 timeline | Delays push a multi tens of billions opportunity to the right | Clear reaffirmation of “H2 2026 ramp, first 1GW deployed by end 2026” | Soft language like “targeting” or “working toward” |

3. 2026 data center growth | Validates (or undermines) the AI ramp thesis | Implied 2026 data center growth >25–30% YoY | Implied growth <25%, or a visible guide down |

4. China export licenses | $800M in charges + ~24% of 2024 revenue still in limbo | Concrete language like “licenses approved” or “in final approval stages” | Continued opacity and boilerplate regulatory language |

5. Gross margin path | Tests the operating leverage story | Commentary that 2026 is “on track toward 55%+ non GAAP gross margin” | Explicit headwinds, or pushing the 55%+ target into 2027+ |

6. ROCm ecosystem progress | Software moat will decide long term AI share | Quantitative updates on ROCm developers, deployments, and ecosystem partners | High level talk with no numbers |

Sources: AMD guidance and commentary; Piper Sandler, Wells Fargo, Zacks, Counterpoint Research

If management can tick two or three of these boxes with concrete, positive disclosures, the market’s tolerance for “high growth + high multiple” likely improves. If the call delivers good numbers but hand‑waves around these specific risks, the current valuation narrative becomes much harder to defend.

The Honest Assessment: Great Company, Demanding Entry Point

EPYC has pulled off a full‑scale comeback in the server market, while Ryzen has outpaced Intel on the consumer side, with data center and PC businesses both firing—giving AMD a genuinely solid fundamental base. MI350 is ramping at a record pace, has already been adopted by multiple cloud providers, and the industry’s capex shift toward AI is creating a real stage for credible alternatives to NVIDIA.

The problem is that the market has already priced in the best‑case script. After a major rally, today’s valuation assumes that new products ramp smoothly, customer concentration eases quickly, and margins move higher—all at the same time.

For existing shareholders, this is a high‑quality name; for new buyers, entering here means paying a premium for a whole set of unresolved uncertainties. Q4 earnings matter, but the real test comes in the second half of 2026: by then, MI450 needs to be in a phase of tangible volume ramp, with at least the first 1GW deployment progressing on a clearly defined schedule, and AMD must demonstrate that the mega‑deal is turning into a broader customer base rather than a single highly concentrated bet.

Until that happens, anyone buying at these levels is effectively paying up for “perfect execution.” And in semiconductors, “perfection” has never had a long shelf life.