Private Credit Funding for AI Data Centers

AI infrastructure development requires an estimated $3 trillion by 2030. While hyperscalers have relied on internal funds, AI ambitions necessitate external financing, with private credit emerging as a primary source over equity and bonds. Private credit, non-bank lending outside public markets, offers flexibility and higher yields but carries risks due to less regulation and opacity. The AI data center build-out is a key driver, with private credit potentially funding a significant portion of capital shortfalls. Despite concerns of a bubble, major tech companies exhibit strong balance sheets, mitigating immediate risks. Investors can explore private equity managers, data center REITs, infrastructure providers, or hyperscalers themselves, each with varying risk-reward profiles.

Introduction

It is already a known fact that the race to build AI infrastructure requires a staggering amount of investment, in fact, the estimates are at around $3 trillion by 2030. The logical question is, where will this money come from?

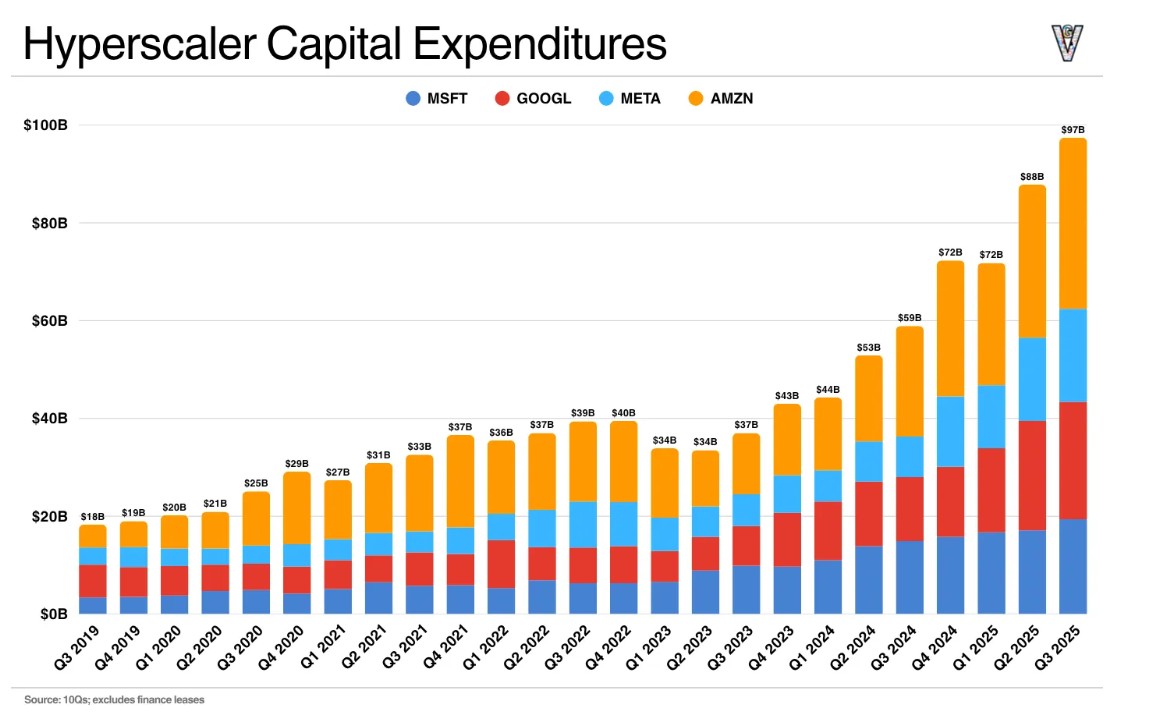

Up until now, the hyperscalers (GOOG, META, AMZN, MSFT) mostly relied on their own balance sheet cash and strong cash flow-generating abilities. We can see a dramatic increase in capex within just five years.

Source: Company Financials, Generative Value

However, the AI ambitions of these companies dramatically outpace their internal finances, and thus, they need to rely on external funding. External financing can come from several sources – equity, public debt (bond) market, and private credit.

Source: Morgan Stanley

As we can see from Morgan Stanley’s graph, the main source of external financing will not come from IPOs or equity offerings; it won’t come from bonds either, but it is very likely to come from private credit. As private credit is not a mainstream topic, there is a brief introduction in the following paragraph.

Private Credit Overview

Private credit refers to non-bank lending that occurs outside public markets or traditional banking systems. Loans are directly originated and held by non-bank institutions, such as private debt funds, rather than being issued as bonds or syndicated through banks. This lack of public trading and reduced regulatory oversight compared to banks makes private credit attractive for borrowers seeking flexible, discreet financing. Businesses, particularly middle-market or private companies, often prefer it to avoid the scrutiny and disclosure requirements of public markets.

However, opacity and lighter regulation introduce higher risks for lenders, including limited transparency and potential for defaults in distressed scenarios. To compensate, private credit typically offers higher yields than traditional fixed-income assets. Returns can sometimes surpass those of conservative, low-risk equities, appealing to investors seeking income in a diversified portfolio.

Source: Ares Management

Private credit traces its roots to the early 1980s, as financial markets grew more sophisticated. This period saw the rise of business development companies (BDCs) and closed-end funds, which provided debt to smaller and growing firms. Before the 2007-2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC), private credit remained a niche, often facilitated by large banks and insurance companies. The GFC transformed the landscape: heightened regulatory scrutiny on banks—through measures like Dodd-Frank and higher capital requirements—curtailed their lending to riskier borrowers. This retreat created opportunities for less-regulated private equity firms and dedicated credit funds to dominate.

Post-GFC, private credit evolved into its modern form, driven by non-bank lenders filling the void in middle-market financing. Today, leading managers by assets under management (AUM) include Apollo Global Management, Ares Management, Blackstone, and others, with platforms often exceeding hundreds of billions in credit-focused AUM.

Source: S&P Global

Estimating the market's size is challenging due to its private nature. As of early 2025, Morgan Stanley estimates the global private credit market at approximately $3 trillion, up from $2 trillion in 2020. The IMF has cited a more conservative $2 trillion figure in prior analyses, highlighting ongoing discrepancies.

The primary investors in private credit are institutional players, such as pension funds, insurance companies, and endowments, channeling capital through private equity firms or direct lending funds. These institutions seek yield enhancement and diversification amid low public bond returns. Private credit's flexibility suits various needs:

- Lending to unlisted private companies, including credit.

- Secured loans with covenants for protection against default, or unsecured for higher risk/reward.

- Distressed debt for companies in financial difficulty.

- Financing for mergers and acquisitions (M&A), including leveraged buyouts.

This versatility has fueled growth, particularly as banks face ongoing constraints.

The private credit market is poised for continued expansion. Morgan Stanley projects growth to $5 trillion by 2029, implying roughly 14% annual compounded growth from the 2025 base of $3 trillion. Emerging sectors like AI infrastructure are key drivers: massive data center buildouts require trillions in capital, with private credit potentially funding over half of the estimated $1.5 trillion global shortfall through 2028. Deals involving hyperscalers (e.g., Meta, Microsoft) have already seen billions deployed via private lenders, highlighting the asset class's role in high-growth areas.

U.S. private credit operates under relatively light regulation compared to banks. Most advisers register with the SEC under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, adhering to fiduciary duties, anti-money laundering (AML) compliance, and custody rules. No heavy banking-style capital requirements apply.

As of late 2025, the Trump administration has pursued broad financial deregulation, aiming to ease burdens on traditional institutions and indirectly support alternatives like private credit. This includes reviews of SEC rules and potential rollbacks, fostering a more permissive environment.

Private Credit and AI Data Center Worlds are Merging

Some of the main attraction points for the hyperscalers to rely on private credit markets are obvious – faster execution, tailored flexible terms, reduced regulations compared to bond issuance, and unlike issuing equity, private credit does not include shareholders’ ownership. Thus, they can swiftly raise funds and spend on GPUs mainly, but also cooling, Power, Construction, Equipment and other infrastructure.

On the other hand, the private equity firms that provide this credit are more than eager to get above-average yields on very reliable borrowers like Meta, Microsoft or Google.

But most importantly, private credit enables "financial engineering" that keeps debt hidden from the mainstream balance sheet of the borrower.

A prime case is Meta's 2025 Hyperion data center campus in Louisiana, the largest private credit deal on record.

- Meta’s Hyperion Data Center Deal (2025) as an example ($27 bn debt + $3 bn equity, total $30bn)

- Meta creates SPV and borrows money from Blue Owl and other investors (PIMCO); Debt is under the SPV; the SPV is co-owned between Meta and BO (20% owned by Meta, 80% owned by BO)

- META pays the SPV to use its data center facilities. On the META balance sheet there is no debt, but META payments to the SPV are recorded as lease expenses; The money the SPV receives are used to repay the interest expenses on the debt

- The terms of the deal are flexible, if things don’t work out, META can leave anytime, they can sell the data center and use the money to repay the debt

Why is it controversial, and what are the fears about potential bubble?

Private credit is, after all, debt, and debt is always associated with financial disasters (The railroad buildup in the 19th century, the great depression in 1930s, the GFC in 2000s) all these crashes were fueled with heavy borrowing that went out of control. This is something AI bears are fear of. Not to mention that private credit, as we discussed above, is less regulated and opaque.

In case of overestimated demand for AI, borrowers (AI scalers) will not have the ability to pay, which will lead to the massive withdrawals from the lenders (the private equity firms) and even ordinary people may suffer because their pension funds are also exposed to this.

But what can trigger a potential bust in the private credit financing for AI data centers? Well, we can think of several factors:

One major catalyst would be persistent inflation leading the Federal Reserve to hike interest rates or maintain a prolonged "higher-for-longer" interest rate environment, as elevated rates increase borrowing costs across the economy, raise debt servicing burdens, and ultimately drive higher default rates, especially in over-leveraged sectors.

Another potential trigger is if major hyperscalers such as Meta, Microsoft, Google, and Amazon decide to slow down their capital expenditures due to insufficient returns on investment, particularly in AI infrastructure, which would cool demand in related credit markets.

Sudden or unexpected regulatory tightening could also play a role, either through stricter financial regulations with greater scrutiny of private credit markets or through new AI-specific rules, potentially driven by political pressures such as calls from parts of the Democratic Party to restrict AI data center expansion.

Intensified competition from China, including breakthroughs from players like DeepSeek, might erode the perceived advantages of U.S. tech leaders, diminish expected future cash flows and make existing debt loads more difficult to sustain.

Finally, a supply glut in critical infrastructure—such as an oversupply of power generation, data center capacity, or related resources—could reduce pricing power and profitability, placing significant pressure on highly leveraged projects and investments.

But how Serious the Debt is?

Let’s assume the estimate from Morgan Stanley is directionally accurate, and there is a $1.5 trillion funding gap for AI-related investments, of which around $800 billion will need to come from private credit.

At first glance, it sounds like an enormous figure, but the picture looks very different when viewed in the context of the four major hyperscalers. In fiscal year 2024, Microsoft, Google, Amazon, and Meta together generated approximately $350 billion in operating income, and for fiscal year 2025, this is projected to rise to around $400–450 billion. Moreover, the average net debt-to-EBITDA ratio for these four companies currently stands at a very comfortable 0.4x–0.5x, indicating minimal leverage and strong balance sheets. By comparison, during the global financial crisis, major banks operated with far higher leverage—for example, Lehman Brothers had an assets-to-equity ratio of around 30–33x. With simple words, the risks the major tech giants are taking with the debt are still much less threatening than what we saw with the banks in the mid-2000s.

Implications for Investors

For investors navigating the potential risks associated with the AI-driven credit expansion and data center build-up, the approach depends on individual risk tolerance. Simply put, if the perceived risks seem excessive, the safest course is to avoid exposure to related stocks altogether. However, for those who still seek exposure while managing downside, several strategies and investment options exist across different levels of risk and involvement. One more complex hedging strategy involves buying instruments like VIX futures or credit default swaps (CDS), which tend to perform better as market volatility and perceived credit risk increase.

Investors could consider stocks of private equity and alternative asset managers such as Blackstone (BX), Apollo Global Management (APO), Blue Owl Capital (OWL), and Brookfield (BN). These firms stand to earn higher yields on loans extended to top-tier companies like Meta, Microsoft, Google, and Amazon. They are among the most directly exposed to a potential AI bubble burst — for instance, Blue Owl holds a majority share in the special purpose vehicle for the Meta-Hyperion deal. In a severe downturn, investor redemptions could shrink assets under management, sharply reduce fee revenue, and drive stock prices lower.

Within this group, exposure varies, with firms like OWL and BX are more heavily involved in AI data center private credit, while others like KKR have less.

An alternative with somewhat lower downside risk is data center REITs, such as Digital Realty Trust (DLR) and Equinix (EQIX). These provide ready-made infrastructure that serves as a complement or substitute for private credit financing. While hyperscalers face the drawback of long-term leasing contracts (typically 10–20 years), these commitments offer REITs a degree of protection through stable cash flows.

REITs are generally managed more conservatively with lower leverage, positioning them for potentially quicker recovery in the event of a bubble burst compared to more highly leveraged private credit providers.

Data center infrastructure providers like Vertiv (VRT), Super Micro Computer (SMCI), and Micron (MU) offer high exposure to the AI build-out boom. Their revenue growth is closely tied to the pace of data center construction, so a sharp slowdown or burst would likely halt growth and pressure valuations. That said, many of these companies currently enjoy multi-year order backlogs, where demand continues to far outstrip supply, providing some near-term cushion.

The large hyperscalers themselves—Meta, Amazon, Google, and Microsoft—remain primary beneficiaries of private credit, as it enables faster scaling without fully burdening their balance sheets. Upside comes from accelerated growth, while risks include higher operating expenses and reduced margins from lease payments, as well as off-balance sheet debt held in special purpose vehicles. Their limited equity ownership in financed projects is offset by exceptionally strong cash generation and robust balance sheets, offering a significant safety buffer. Smaller-scale cloud providers (sometimes called "neo-clouds," such as CoreWeave or similar emerging players) follow a similar dynamic to the big hyperscalers but with amplified risk and reward. They tend to rely more heavily on debt financing due to currently limited cash flow generation and weaker balance sheets, making them more vulnerable in a downturn. On the upside, their smaller size and early growth stage offer greater potential returns if the build-out continues unabated.

Finally, credit rating agencies—primarily Moody's Corporation (MCO) and S&P Global (SPGI)—benefit directly from increased debt issuance. The more private and public debt created for data centers, the greater the demand for initial ratings and ongoing surveillance, driving revenue higher in this near-duopoly market. Their downside appears quite limited, as they do not hold or bear the credit risk of the debt they rate.