Who is Who in China E-Commerce, Quick Commerce, and Food Delivery Sectors

China's e-commerce sector is at an inflection point, transitioning from intense price wars to a more rational, profitable phase. Traditional e-commerce is projected to grow 8-10% annually, with Alibaba leading market share, followed by JD.com, Pinduoduo, and Douyin, each distinct in their positioning. Quick commerce and food delivery are expected to grow rapidly, with Meituan as the incumbent leader, though Alibaba and JD are closing the gap. Key trends include AI integration, vertical integration into infrastructure, and international expansion. Investors should note that while competition will likely decrease, Alibaba and JD.com appear best positioned long-term, with Pinduoduo and Meituan facing more structural challenges.

Source: TradingView

Introduction

The e-commerce industry in China has always been one of the most (if not the most) important industries in the country, which has always been attracting a lot of investors’ attention. But why? There are two reasons for this. First of all, e-commerce has always been a reflection of the overall economy of the country and the general consumer sentiment. Secondly, the e-commerce giants are some of the most technologically advanced companies in the country. Think of them as pioneers in almost every innovation in the country’s corporate world: AI, logistics robots, livestream selling, you name it.

The e-commerce sector, as we see it now, is at an inflexion point. The last few years have been brutal: insane subsidy wars, margins crushed to zero, market share swinging wildly every quarter. Therefore, the current e-commerce players are at the crossroads between continuing the intense price competition and entering a more rational, more profitable phase.

And when we talk about e-commerce, it is not just about buying sneakers on Taobao, we should also cover the areas of food delivery, the emerging quick commerce and any other trends associated with it.

Traditional E-commerce

Traditional e-commerce remains the bedrock of the consumer internet economy. It is not easy to gauge the exact size of the domestic e-commerce spending, but according to some estimates, in 2024, the total gross merchandise value was around 15 trillion RMB. Currently, the e-commerce penetration is standing at around 45% of the total retail sales. We do expect e-commerce spending to grow at a higher rate than offline spending, perhaps 8-10% per year, as users would opt for a smoother online experience and further penetration in lower-tier cities and rural areas of the country.

Just 10 years ago, the industry used to be dominated by a duopoly of Alibaba and JD.com, but in recent years things have changed dramatically. Alibaba, through the combination of Taobao and Tmall, continues to hold the dominant position with roughly a 35 % share. Pinduoduo and JD.com each command around 20 %, Douyin has surged to approximately 15 %, and the remaining 10 % is split among Vipshop, Kuaishou, and other smaller platforms.

How did Pinduoduo and Douyin pull this off? The ascendance of Pinduoduo and Douyin was not accidental; Pinduoduo was able to attract price-conscious consumers and, at the same time, charge merchants extra-low take-rates. On the other hand, Douyin successfully leveraged its vast social media empire to ride the trend of livestream shopping.

Despite the overlap in products, we can still see a certain distinction in the e-commerce players’ positioning. JD.com has deliberately cultivated a premium image with higher average selling prices and a customer base skewed toward tier-one and new-tier-one cities. Alibaba remains the undisputed champion of assortment breadth and occupies the middle-price sweet spot, offering everything from luxury goods on Tmall to everyday essentials on Taobao. Pinduoduo continues to own the value-for-money segment and lower-tier geography, while Douyin drives explosive but often impulsive purchases through entertainment and live-streaming.

The above segmentation is also reflected in the take rates the e-commerce players charge merchants and shoppers, as a percentage of the transaction. JD.com extracts the highest monetization at 8–10 % because it operates its own nationwide logistics network. Douyin’s effective take rate also lands in the 5–10 % range, though a large portion comes from live-streaming service fees rather than pure advertising or transaction commissions. Alibaba sits in a comfortable middle ground at 3–5 %, Pinduoduo also runs at low levels of 4-5 % and that includes an astonishingly low commission charged to merchants of 1% (a direct consequence of the overwhelming strength of Pinduoduo in lower-tier cities where merchants and shoppers are far more price-sensitive and only willing to accept razor-thin platform fees, explaining).

We would like to pay special attention to the loyalty program penetration.

Alibaba’s 88VIP program has already surpassed 50 million paying members, yet this still represents only about 5 % of its active user base, a fraction of Amazon Prime’s 75 % penetration in the United States. JD Plus trails with roughly 35 million members, with a similar penetration rate to its total user base. As these programs mature, they create far stickier shopping habits and increase the average order volume.

Quick Commerce and Food Delivery

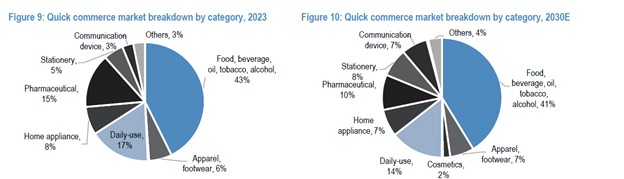

Quick Commerce emerged on the back of traditional e-commerce. Quick commerce is the delivery of food and non-food items within a very short period of time, often within 30-60 minutes, which is much faster than what conventional e-commerce used to offer (a couple of days). It primarily includes perishable items like food (meat and groceries), beverages (bubble tea, coffee), tobacco, alcohol, but also daily necessities, pharmaceuticals, home appliances and even clothes and electronics.

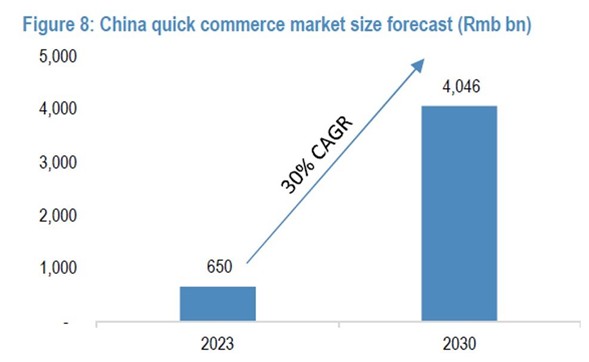

Source: JP Morgan

Source: JP Morgan

According to JP Morgan, the quick commerce market is expected to grow 30% on average in the coming five years, reaching around 4 trillion RMB, including food delivery. This hyper-fast growth will come from both cannibalising the traditional e-commerce product lines (more customers will opt for quicker delivery) and also from newly created demand.

The food-delivery market generated approximately 1.5 trillion renminbi in 2024 and is expected to grow at around 10 % annually as it continues penetrating the remaining 70 % of restaurant sales that still happen offline or through proprietary channels.

4 trillion RMB is, in fact, quite lucrative, and it means an enormous amount of revenue and profit. Even Alibaba this week has publicly stated its intention to reach 1 trillion renminbi of platform quick-commerce GMV within the next three years.

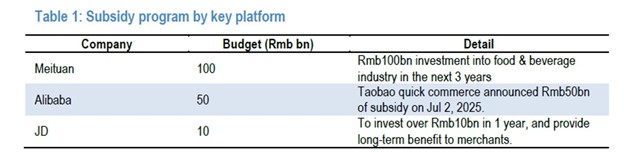

This is why, in order to capture this, e-commerce players are spending and planning to spend on merchant discounts, consumer subsidies, acquiring riders and investing in related infrastructure.

Source: JP Morgan

Who’s winning right now? In quick commerce and food delivery, Meituan remains the incumbent leader with a 50–60 % share, followed by Alibaba (formerly Ele.me, now fully integrated into Taobao Instant Commerce) at 25–30 % and JD at a fast-growing but still modest 5–10 %, which recently entered the food delivery market.

Meituan still enjoys some structural advantages with roughly 7 million riders and the industry’s most refined 30-minute delivery algorithm and a deep penetration in the small stores and restaurants, but Alibaba and JD are closing the gap.

What makes BABA and JD formidable competition for Meituan is the fact that they can leverage their traditional e-commerce business and grow their quick commerce operations on the back of it. Alibaba is closing the gap rapidly with nearly 5 million riders and the ability to cross-leverage traffic, data, and fulfilment assets from its broader ecosystem, while JD is utilising its top-notch logistics infrastructure.

Another important observation is that Meituan still charges the highest rates for quick commerce (15-20%) versus BABA (12–18 %) and JD (10–15 %). We believe that it is difficult for Meituan to further lower take rates because their revenue is much more tied to quick commerce, unlike BABA and JD, who have a mature, profitable cash cow business to support the subsidies they are giving. Not to mention that the balance sheets of BABA and JD are healthier than that of Meituan.

What are the trends?

Several secular trends are reshaping the industry and the competitive dynamics.

AI everywhere

The race for AI adoption globally can also be seen in China. More or less, all e-commerce players would like to implement AI in their daily business operations, but so far, Alibaba has reached the furthest. Alibaba already implements tools that help merchants automate the selling process and also improve the recommendation algorithm for shoppers.

On the other hand, JD’s AI efforts remain more narrowly focused on logistics and warehouse automation, an area where it already enjoys a structural advantage.

Vertical Integration

Vertical integration into physical infrastructure is another main theme, whether it is physical stores or dark warehouses, expanding offline footprint is essential for anyone serious about instant delivery.

For instance, Alibaba is developing its supermarket Freshhippo. JD is planning to build 10,000 kitchens specifically catering for the food delivery business. Meituan is following this strategy.

This is a swift transition for BABA JD and Meituan, as they are moving away from mere intermediaries to more integrated businesses. The benefits of this are the ability to lower prices for consumers, ensure product quality and also improve the delivery speed.

On the other hand, amid this process of integration of logistics and suppliers, Douyin may face more of an uphill path. Douyin was able to grab significant market share in recent years, but its reliance on third-party logistics infrastructure (they use JDL, Dada, SF and ZTO) may put them in a less advantageous position.

Going Global

International expansion is a good opportunity for Chinese e-commerce giants to move away from the fierce domestic competition and diversify their revenue sources. Alibaba possesses by far the strongest overseas footprint through the cross-border platform AliExpress, Lazada’s dominance in Southeast Asia, and Trendyol in Turkey. Pinduoduo’s Temu has also become a global phenomenon in its own right, briefly becoming one of the top platforms overseas. Even non-listed peers like Douyin and Shein are emphasising global presence.

Also, despite having less of an international operation, JD is building warehouses in the Middle East and opening physical stores in Europe, and even Meituan is testing its Keeta brand in selected Middle Eastern markets.

The benefit here is the potential many markets possess, as the e-commerce habits in China are quite well-established; we cannot say the same for other markets globally. The domestic giants can utilise their superior know-how and tap into the higher growth of these markets. But on the flipside, international expansion always comes with a large upfront investment related to establishing infrastructure, onboarding merchants and marketing campaigns to attract users; not to forget the elevated regulatory risk and compliance considerations.

Involution

Perhaps the single most important near-term catalyst is the likely end of extreme “involution.” The current subsidy war across quick commerce and food delivery is not sustainable indefinitely. As consumer confidence continues to recover and stimulus flows through the economy, platforms will be able to dial back incentives without losing volume. When that happens, unit economics will improve dramatically, margins will re-expand, and the profitability of the entire sector will enter a new, far healthier phase.

The exact timing of this is hard to predict. In the recent earnings from JD and BABA, we saw the cash burn to be still quite significant; however, both companies predict that we are at the peak of the spending, and from now on, we will gradually see a downward trend.

What to be Aware as an Investor

From an investment perspective, we believe that sooner or later the market will stabilise and there will be less competition (hence less incentives). The e-commerce market of China is big enough for several players, so we do not see any of the market players to be existentially threatened.

However, Alibaba and JD.com appear best positioned over a multi-year horizon. JD benefits most directly from any consumption upgrade cycle, given its premium positioning and higher take rate, while Alibaba combines unmatched ecosystem breadth, loyalty-program runway, AI leadership, and global scale. Pinduoduo remains heavily exposed to the low-end cohort and could lose share fastest if consumers begin trading up. Meituan finds itself in the most structurally difficult position: it is still overly reliant on food delivery for both revenue and profit, carries the highest take rates it must defend, and lacks the diversified traffic sources that Alibaba and JD enjoy.

Even after the strong rally Chinese internet stocks have enjoyed in 2025, valuation gaps versus global peers remain striking, as we can see from the table below. As competition rationalises, subsidies moderate, and profitability will accelerate.

Source: Yahoo Finance