De-dollarization Is Unlikely to Ensure a Long-term Weakening of the U.S. Dollar Index

The de-dollarization process, driven by factors like U.S. tariff policy and Fed policy erosion, has accelerated but its long-term impact on the U.S. Dollar Index remains uncertain. Historical data shows a weak correlation between reserve share changes and the Index. Four key rationales explain this divergence: gold prices don't necessarily weaken the dollar; rising gold reserves are valuation-driven, not just purchases; de-dollarization definitions are narrow, excluding payments and transactions where the dollar remains dominant; and robust private sector capital inflows into USD assets indicate sustained demand. Therefore, de-dollarization may cause short-term pressure but doesn't guarantee a long-term dollar decline.

Executive Summary

Driven by the combined effects of multiple factors—such as the frequent adjustments to U.S. tariff policies, the erosion of the Federal Reserve's policy independence, and the widening rifts in the U.S. dollar credit system—the de-dollarization process has accelerated, which in turn has contributed to the sustained downward trend of the U.S. dollar exchange rate over the past year. Against this backdrop, many economists point out that the further deepening of de-dollarization, coupled with the decline in the global share of U.S. dollar foreign exchange reserves, will exert persistent downward pressure on the U.S. Dollar Index. In this regard, our view is as follows: in the short-to-medium term, factors related to de-dollarization will indeed exert periodic constraints on the U.S. dollar exchange rate; however, from a long-term perspective, there remains considerable uncertainty regarding their actual impact on the trend of the U.S. Dollar Index.

Looking back at history, the earliest proposals related to de-dollarization can be traced to the period of the 2008 global financial crisis, while the de-dollarization process with substantive significance officially kicked off in 2017. From the first quarter of 2017 to the fourth quarter of 2021, the core driving logic of de-dollarization during this phase was the expansion in the proportion of non-US dollar reserve currencies. This round of multipolar evolution of the international reserve system exerted significant downward pressure on the US Dollar Index. Since 2022, the multipolar shift of the international reserve asset system has been led primarily by gold. Against this backdrop, instead of declining in tandem with the drop in the share of US dollar reserves, the US Dollar Index has trended upward against the prevailing tide. Empirical data from the above two phases fully demonstrate that there is only a weak correlation between changes in the share of US dollar reserves and the movements of the US Dollar Index.

If a systematic analysis is conducted using the period from 2008 to the third quarter of 2025 as a complete observation cycle, the evolution of the US dollar’s reserve status and the performance of the US Dollar Index (in terms of strength and weakness) exhibit an extremely prominent divergence. It follows that, from a long-term to ultra-long-term perspective, conclusions drawn about the future movements of the US Dollar Index based solely on the single dimension of the deepening de-dollarization process lack sufficient and reliable supporting evidence.

The continuous deepening of the de-dollarization process does not readily lead to the conclusion that the U.S. Dollar Index will enter a long-term downward trajectory, and the core supporting logic behind this proposition can be summarized into the following four points. First, a stronger gold price is not necessarily equivalent to a weaker U.S. Dollar Index. The reason lies in the fact that the construction framework of the U.S. Dollar Index is weighted primarily by the U.S. dollar’s exchange rates against six major currencies. While the U.S. economy faces inherent structural imbalances, economies issuing other major currencies are also grappling with their respective endogenous challenges. In the foreseeable future, no single currency is capable of posing a substantive challenge to or replacing the dollar’s dominant status. Second, the rise in the share of global gold in international reserves is not primarily driven by the active gold-purchasing behavior of central banks around the world, but rather mainly by the valuation effect generated by the upward movement of international gold prices. Should gold prices experience an unexpectedly sharp decline in the future, triggering a negative valuation effect, the share of the U.S. dollar in international reserves is expected to rise passively—a development that may provide certain upward support for the U.S. Dollar Index.

Third, the current definitional scope of de-dollarization is relatively narrow. Existing research mostly confines it to the single dimension of international reserve currencies. However, if a broader definition is applied to de-dollarization, incorporating two other core scenarios—international payments and foreign exchange transactions—into the consideration set, then the phenomenon of de-dollarization under this broad measure may not have a genuine basis for existence. Finally, despite the fact that overseas capital from government sectors has registered a net reduction in holdings of U.S. dollar assets in recent years, overseas capital from private sectors has continued to increase their holdings of U.S. dollar assets on a large scale. This structural feature fully indicates that from the aggregate perspective (government plus private sectors), overseas capital’s willingness to allocate to U.S. dollar assets has not diminished, and market demand remains robust.

To sum up, through combing the historical context (presenting the facts) and conducting an in-depth theoretical analysis (providing the rationale), we conclude that, from a long-term perspective, it lacks sufficient and reliable supporting conditions, and the conclusion is untenable to infer that the U.S. Dollar Index will show a sustained weakening trend solely on the basis of de-dollarization as the core criterion.

Recent Development

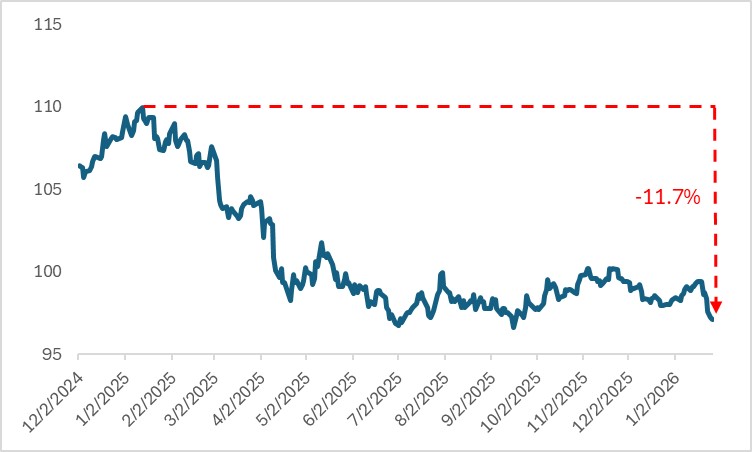

Driven by the combined effects of multiple factors—including the frequent adjustments to U.S. tariff policies, the erosion of the Federal Reserve’s policy independence, and the widening rifts in the U.S. dollar credit system—the accelerated de-dollarization process has contributed to a sustained downward trend of the U.S. dollar exchange rate over the past year. The U.S. Dollar Index has retreated from the year-to-date high of 109.96 in early 2025 to the current level of 97.13, representing a cumulative decline of 11.7%.

One of the most intuitive indicators for measuring de-dollarization is global U.S. dollar foreign exchange reserves. According to data disclosed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), as of the end of the third quarter of 2025, the global share of U.S. dollar foreign exchange reserves had dropped to 56.9%. This proportion has remained below the 60% threshold for more than 40 consecutive months, hitting a record low since 1999. In the first three quarters of 2025, the share of such reserves registered a cumulative decline of 1.6 percentage points, marking the steepest year-to-date drop since 2003.

Based on the aforementioned trend, most economists point out that the deepening de-dollarization process, or the evolving pattern of the global monetary system toward multipolarity, will exert sustained downward pressure on the U.S. Dollar Index. In this regard, our view is that in the short-to-medium term, de-dollarization factors will indeed suppress the U.S. dollar exchange rate; however, from a long-term perspective, there remains considerable uncertainty regarding their actual impact on the U.S. Dollar Index.

Figure: U.S. Dollar Index

Source: Refinitiv, TradingKey

2008–2016

By tracing the historical evolution and data trajectory, we can draw an intuitive conclusion: the earliest initiatives related to de-dollarization can be traced back to the 2008 global financial crisis. The full-blown outbreak of the crisis at that time triggered in-depth reflection across the international community on the existing international monetary system anchored in U.S. dollar credit. This global financial crisis fully exposed the endogenous flaws and systemic risks inherent in the prevailing international monetary system. Against this backdrop, policymakers and mainstream economists around the world reiterated the core value of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), pointing out that SDRs can effectively circumvent the structural defects inherent in using a single sovereign credit currency as a reserve currency, and thus represent an ideal direction and core objective for advancing the reform of the international monetary system.

However, despite the growing market attention on SDRs, the de-dollarization process stagnated for as long as eight years. At the end of 2016, the global share of U.S. dollar foreign exchange reserves still stood at 64.7%, representing a 1.8-percentage-point increase compared with the end of 2008. It was not until after 2017 that the share of U.S. dollar foreign exchange reserves officially entered a downward trajectory. The core reason behind the delayed progress of de-dollarization lies in the fact that, following the outbreak of the 2008 global financial crisis and the 2012 European sovereign debt crisis, the U.S. dollar’s safe-haven asset attribute was further highlighted, and the demand for it as a safe haven rose instead of falling. Against the backdrop of elevated uncertainty in the global economy and financial markets, governments around the world continued to increase their holdings of U.S. dollar assets to safeguard liquidity security and asset stability. Correspondingly, the U.S. Dollar Index also showed a notable upward trend during this period, climbing from 81 at the end of 2008 to 102 at the end of 2016.

2017–2021

The de-dollarization process in the true sense of the term began in 2017. From the first quarter of 2017 to the fourth quarter of 2021, the multipolar evolution of the international reserve asset system (encompassing gold reserves and foreign exchange reserves) was driven primarily by the rise of non-U.S. dollar reserve currencies. During this period, the share of gold reserves increased by 3.5 percentage points, a magnitude smaller than the 6.8-percentage-point decline in the share of U.S. dollar reserves over the same period. Among non-U.S. dollar reserve currencies, the shares of the euro, Japanese yen, British pound, Canadian dollar, Australian dollar and Chinese yuan all rose to varying degrees, with the exception of a slight drop in the share of the Swiss franc.

Given that the core driver of de-dollarization during this phase was the expansion in the share of non-U.S. dollar reserve currencies, this round of multipolarization in the international reserve system exerted downward pressure on the U.S. Dollar Index. Over the five-year period from the start of 2017 to the end of 2021, the U.S. Dollar Index recorded a cumulative decline of 6.3%.

Post-2022

Since 2022, the multipolar evolution of the international reserve asset system has shifted to be driven primarily by gold. Following the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, Western countries imposed joint financial sanctions on Russia, exposing traditional foreign exchange reserve assets to severe security risks. This external shock directly accelerated the multipolarization of the international reserve asset system.

As of the end of the third quarter of 2025, the share of gold reserves had surged by 11.9 percentage points compared with the end of 2021, a notable increase that significantly outpaced the 8.9-percentage-point decline in the share of U.S. dollar reserves over the same period. Meanwhile, the shares of the other five major reserve currencies all dropped to varying degrees.

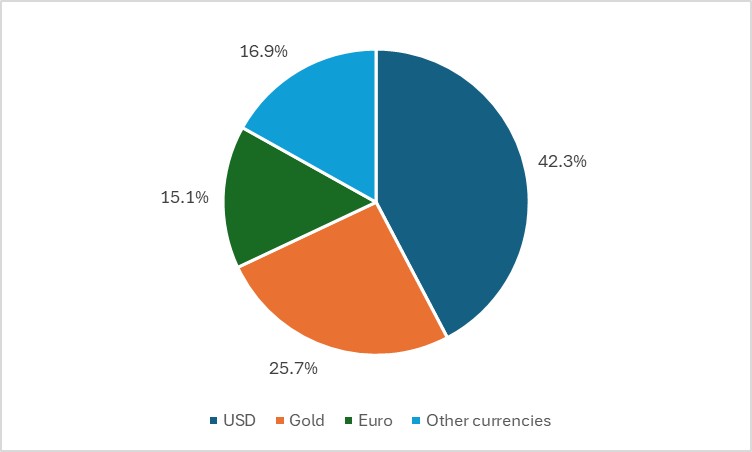

Notably, since the fourth quarter of 2023, the scale of global gold reserves has surpassed that of the euro, making gold the world’s second-largest international reserve asset after the U.S. dollar. As of the end of the third quarter of 2025, the shares of the three major reserve assets—U.S. dollar, gold and euro—stood at 42.3%, 25.7% and 15.1%, respectively.

Figure: Shares of U.S. Dollar, Gold and Euro Reserves as of the End of Q3 2025

Source: Refinitiv, TradingKey

Given that the current round of multipolarization in the international reserve asset system is dominated by gold, the U.S. Dollar Index has trended upward rather than declining in tandem with the drop in the share of U.S. dollar reserves. From the start of 2022 to the third quarter of 2025, the U.S. Dollar Index posted a cumulative gain of 1.9%.

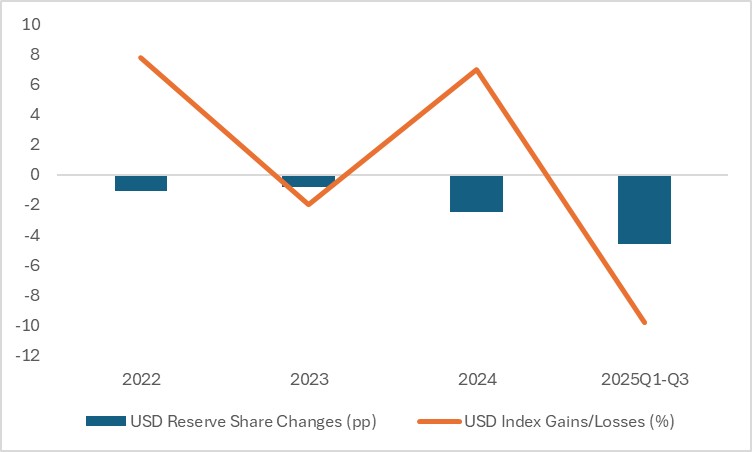

Breaking down the performance by sub-period, in 2022, 2023, 2024 and the first three quarters of 2025, the share of U.S. dollar reserves in the total volume of international reserves (including gold reserves) fell by 1.1, 0.8, 2.5 and 4.6 percentage points respectively, while the corresponding year-on-year changes in the U.S. Dollar Index stood at 7.8%, -2.0%, 7.0% and -9.8%. The aforementioned data indicate that there is only a weak correlation between changes in the share of U.S. dollar reserves and the movements of the U.S. Dollar Index.

Figure: Correlation Between U.S. Dollar Reserve Share and U.S. Dollar Index

Source: Refinitiv, TradingKey

Ultra-Long-Term Historical Perspective

If we conduct an analysis using the period from 2008 to the third quarter of 2025 as a complete observation cycle, a more prominent divergence can be observed between the evolution of the U.S. dollar’s reserve status and the performance (strength or weakness) of the U.S. Dollar Index.

Over this 17-year time horizon, the share of the U.S. dollar in foreign exchange reserves recorded a cumulative decline of 6 percentage points; when measured against the broader gauge of international reserves (including gold), the magnitude of the U.S. dollar’s share decline widened further to 14.3 percentage points. In stark contrast, the U.S. Dollar Index posted a cumulative gain of 20.5% over the same period, moving against the prevailing trend of the dollar’s falling reserve share. Among the component currencies of the U.S. Dollar Index, all five core currencies—with the exception of the Swiss franc—registered varying degrees of depreciation.

In summary, from a long-term to ultra-long-term perspective, conclusions drawn about the trend of the U.S. Dollar Index based solely on single-dimensional factors such as the deepening de-dollarization process and the weakening of the U.S. dollar’s reserve status lack reliable substantiation.

Reason 1 for the Divergence Between De-dollarization and the U.S. Dollar Index: A Stronger Gold Does Not Equate to a Weaker U.S. Dollar Index

The deepening of the de-dollarization process does not readily lead to the conclusion that the U.S. Dollar Index will enter a long-term downward trajectory, which can be attributed to four core supporting rationales. First, as noted earlier, the de-dollarization process since 2022 has actually been driven by the expansion of gold reserves. Although theoretically there is a negative correlation between gold prices and the U.S. dollar exchange rate, gold is still priced and settled primarily in U.S. dollars. Central banks around the world also need to use the U.S. dollar as the medium of exchange and unit of account when conducting gold purchase operations. Even if gold prices maintain a strong trend in the future, which may exert certain pressure on the value of the U.S. dollar against gold, this does not mean that the U.S. dollar will depreciate against other major currencies.

Beyond the fact that the dollar’s central position in the gold trading system is unlikely to be shaken in the short term, another key reason is that the construction logic of the U.S. Dollar Index is inherently weighted by the dollar’s exchange rates against six major currencies. It is worth noting that while the U.S. economy and financial system certainly have structural issues, economies issuing other major reserve currencies are also confronted with their respective endogenous challenges. In the foreseeable future, no single currency is capable of posing a substantive challenge to or replacing the dollar’s dominant status.

Reason 2: The Real Driver Behind the Rising Share of Gold in Reserves

The core driver of the growing share of global gold in international reserves is not primarily the active gold-purchasing behavior of central banks worldwide, but rather mainly the valuation effect generated by the rally in international gold prices. From a data perspective, the global gold reserve balance registered a cumulative increase of $2.44 trillion from the first quarter of 2022 to the third quarter of 2025. During this period, global central banks recorded a net purchase of 3,854 tonnes of gold in total. Based on the average quarterly London spot gold price, the corresponding value of these purchases stood at $301.9 billion, accounting for a mere 12.3% of the total growth in the global gold reserve balance over the same period.

Against the backdrop of the sharp rally in international gold prices, economists can hardly conclude that there is absolutely no bubble risk in the gold market. Should gold prices experience an unexpectedly sharp correction in the future, triggering a negative valuation effect, the share of the U.S. dollar in international reserves is expected to rebound passively, which may in turn provide an upward impetus to the U.S. Dollar Index.

Reason 3: The Definition of De-dollarization Is Excessively Narrow

From the perspective of international reserve currencies, the evolving trend of de-dollarization is indeed an indisputable fact. However, a vastly different market landscape may emerge if we analyze the issue from the angles of international payments and foreign exchange transactions.

According to statistics released by SWIFT, the dollar accounted for an average of 48.2% of global international payment currencies in the first 11 months of 2025, representing an 8.8-percentage-point increase from the 2021 level. Meanwhile, the latest sampling survey conducted by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) shows that the share of the dollar in the global foreign exchange market’s average daily trading volume has further climbed from 88.5% in 2022 to 89.2% in April 2025.

In summary, if we adopt a broader definition of de-dollarization—one that comprehensively considers the three core dimensions of international payments, foreign exchange transactions, and international reserves—then the phenomenon of de-dollarization under this broad measurement may not truly exist, or at least has not developed to a notable extent.

Reason 4: Look Beyond Government Sectors to Private Sectors

Since 2025, while overseas capital from government sectors has posted net reductions in holdings of U.S. dollar assets, overseas capital from private sectors has continued to substantially increase their holdings of such assets. According to data disclosed in the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Treasury International Capital (TIC) Report, in the first three quarters of 2025, net capital outflows from overseas official sectors reached $4.3 billion, whereas net capital inflows from overseas private sectors soared to $1.13 trillion, representing a year-on-year surge of 85.9%.

If we extend the observation time horizon, the average annual net inflow of U.S. international capital (covering both government and private sectors) reached $1.23 trillion during the 2022–2024 period, representing a doubling of the average recorded in the 2017–2021 period. Among this total, the average annual net inflow of overseas capital from the private sector hit as high as $1.12 trillion, accounting for 91.1% of the overall net international capital inflows. This data characteristic fully indicates that from a total volume perspective, overseas capital’s willingness to allocate to U.S. dollar assets has not diminished, and market demand remains robust.

Conclusion

All in all, drawing lessons from history, the evidence from the period spanning 2008 to the third quarter of 2025 demonstrates that the de-dollarization process cannot be verified as the core factor driving the weakening of the U.S. dollar. The underlying reasons are mainly reflected in four aspects: the correlation between gold prices and the U.S. Dollar Index is relatively weak; the driving logic behind the rising share of global gold in international reserves deviates from common market expectations; the existing definitional scope of de-dollarization is excessively narrow, failing to fully cover core scenarios; and the sustained net inflow of overseas capital from the private sector provides support for U.S. dollar assets.

On this basis, we judge that although de-dollarization will likely continue to exert periodic downward pressure on the U.S. Dollar Index by influencing market sentiment in the short-to-medium term, it lacks sufficient and reliable support to conclude that the U.S. Dollar Index will weaken sustainably based solely on de-dollarization as the core criterion from a long-term perspective, and such a conclusion is untenable.