From the Internet Revolution to the AI Bubble: What Is the Real Threat to U.S. Stocks?

The AI investment boom mirrors the internet bubble of the late 20th century, characterized by hype around "paradigm shifts" and overheated infrastructure investment. Similar to the dot-com era, AI valuations appear disconnected from fundamentals, with a fierce arms race for computing resources and a mismatch between technological expectations and practical application. The Federal Reserve's policy, historically influenced by economic shocks like the Russian debt crisis (internet bubble) and currently by job market weakness, has postponed interest rate hikes, potentially allowing the AI bubble to inflate further over the next two years. Investors are advised to exercise caution.

Can the tides of the past internet era offer practical insights into the current debates surrounding the AI industry bubble? Why does every wave of technological revolution give rise to large-scale asset bubbles? What role has the Federal Reserve’s policy regulation played in the formation and evolution of stock market bubbles? This paper will trace the historical course of the internet revolution and conduct an in-depth analysis of each of these questions one by one. First of all, it will review the trends of the U.S. stock market from 1995 to 2000, and it is not difficult to find that the development trajectory of the internet industry back then was almost identical to the current development momentum in the AI field.

How Strikingly Similar the Bubble Origins Are

The internet boom from 1995 to 2000 was almost identical to the current investment frenzy in artificial intelligence. The outbreak of the current AI investment boom started with the launch of ChatGPT in 2023, after which investors across the market began to focus extensively on investment opportunities in the AI field. The internet boom back then also had a triggering event—Netscape, founded in 1993. The emergence of this company brought the internet concept directly into the public eye. Netscape’s core competitive edge lay in developing the world’s first web browser. Its epoch-making significance is comparable to how ChatGPT today has driven the popularization of AI technology with its intelligent chat application; it was precisely by virtue of the browser—a critical vehicle—that Netscape enabled internet technology to truly integrate into the daily lives of the general public.

This disruptive innovation endowed the Internet with tangible commercial value. In turn, Netscape’s business performance witnessed leaping growth—just one year after its founding in 1993, its user base exceeded 10 million by 1994.Driven by Netscape’s demonstration effect, leading tech companies of that era scrambled to focus their layout on the Internet track, with Microsoft being the most representative one. Starting from 1995, Microsoft officially adjusted its development strategy and went all out to expand its Internet business. Guided by this industry giant, a host of leading tech enterprises successively kicked off their transformation into the Internet sector. Thanks to the collective strategic transformation of tech companies, the U.S. stock market was strongly boosted: the tech sector surged by as much as 60% in the first half of 1995, outperforming the overall market performance significantly during the same period. Looking back at the current market landscape, the historical logic is almost replicated exactly: first, Microsoft took the lead in investing in OpenAI, followed by Google, Meta, Apple and other tech giants that successively entered the AI field, jointly driving the stock prices of the tech sector to stage a strong upward trend.

An In-depth Comparison of These Two Bubbles

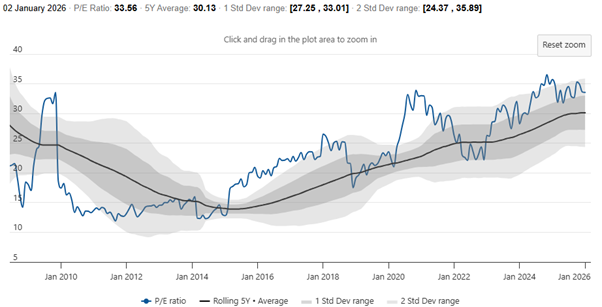

Although there are slight differences between the formation of the internet bubble and the current AI investment boom in the phase of rising asset valuations, their developmental trajectories are almost identical. The primary common feature is that the grand narrative of “paradigm shift” has been overhyped, which in turn has led to asset valuations becoming severely disconnected from fundamentals. In 1999, the Nasdaq Composite Index surged by as much as 85% for the full year; by 2000, when the internet bubble peaked, the average price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio of the index’s constituent stocks once soared to 175 times. Amid the market frenzy back then, a company could see its market capitalization multiply simply by adding “.com” to the end of its name. The current AI boom is similarly enveloped in the narrative framework of “artificial intelligence reshaping productivity”. According to relevant data from Goldman Sachs, among the components of the S&P 500 Index in 2024, companies that mentioned AI-related businesses in their earnings reports or announcements significantly outperformed those that did not reference the AI concept in their stock price performance. While the overall P/E ratio of the Nasdaq 100 Index currently stands at around 34 times, far below the extreme levels seen during the 2000 internet bubble, the price-to-sales (P/S) ratio of some leading enterprises in the AI sector has exceeded 30 times. This kind of blind enthusiasm for a single technological path is virtually indistinguishable from the market performance during the internet bubble era.

Figure: P/E Ratio of the Nasdaq 100 Index

Source: Refinitiv, TradingKey

The second similarity lies in the overheated investment in infrastructure and the industry-wide arms race. During the internet bubble era, the total length of optical fibers laid worldwide exceeded 100 million miles. Cisco’s market capitalization surged to $555 billion in 2000, with its price-to-earnings ratio even surpassing the 100x threshold. However, subsequent market demand failed to keep pace with the speed of capacity expansion, leaving 95% of the optical fibers idle, and Cisco’s stock price consequently plummeted by 80%. Amid the current AI wave, the market is trapped in a fierce scramble for computing resources, with NVIDIA taking on the role that Cisco played back then. Its AI chip business has posted a year-on-year revenue growth of over 400% for several consecutive quarters. According to estimates by Barclays, the combined capital expenditure of the four major cloud computing giants—Microsoft, Amazon, Google and Meta—will exceed $200 billion in 2024, the vast majority of which is being funneled into the AI chip sector. Sequoia Capital once put forward an influential proposition known as “the $600 billion question”: For every $1 invested in AI infrastructure, it typically requires $2 in software revenue to break even. Yet judging from the current market reality, the actual revenue scale at the AI application level is only in the tens of billions of dollars, creating a glaring and undeniable performance gap between it and the astronomical infrastructure investment.

The third similarity is the mismatch between technological expectations and real-world development, as revealed by Amara’s Law. At the peak of the internet bubble in 2000, investors widely believed that e-commerce would rapidly replace offline physical retail. However, the e-commerce penetration rate in the U.S. stood at a mere 0.8% back then, and the supporting payment systems and logistics networks were far from mature, ultimately consigning a large number of internet startups to an unceremonious exit. The current AI industry is similarly trapped in a phase of overestimating the short-term value of technology. While ChatGPT has already amassed a user base of 850 million to 900 million, enterprises still have to confront multiple hurdles—such as legal compliance and data privacy protection—in the process of commercializing AI technologies. Beyond that, although some technologies demonstrate impressive advantages in theory, they expose critical flaws of insufficient efficiency in practical applications, creating a classic predicament of technological illusion.

Ultimately, history often unfolds along similar evolutionary trajectories. Whether it was the internet wave of the late 20th century or the current AI boom, the essence of asset bubbles remains unchanged—it stems from capital’s eagerness to seize the first-mover advantage and place premature bets on a technological revolution capable of driving a leap in productivity. The ongoing AI investment frenzy is certainly underpinned by tangible revenue growth, as evidenced by the substantial profit expansion of NVIDIA. However, several factors are sending warning signals to the market: the herd mentality-driven euphoria fueled by the Fear of Missing Out (FOMO) pervasive in the market, the reckless leveraged investment in infrastructure, and the practical predicament where the monetization pace of AI applications lags far behind the speed of infrastructure expansion. All these factors indicate that when the hype around an industrial narrative far outstrips the ability of fundamentals to deliver, the rational regression of valuations may be delayed—but it will never fail to arrive.

Why Do Technological Revolutions Trigger Stock Market Bubbles?

Objectively speaking, almost all technological revolutions of the caliber of the Internet and artificial intelligence will invariably give rise to large-scale asset bubbles. Essentially, technological revolutions themselves are inherently prone to fueling bubbles, with the core logic boiled down to three points. First, the driving effect of technological revolutions on corporate profits tends to exhibit prominent short-to-medium-term characteristics. In the early stages of a technological revolution, corporate profitability usually experiences explosive growth, yet such high profit growth rates are unsustainable in the long run. The reason is that once some enterprises reap excess profits by virtue of new technologies, they will quickly attract a flood of market participants to follow suit, thereby triggering cut-throat competition across the industry; as competition intensifies, the original room for excess profits will be continuously squeezed. Notably, however, investors tend to underestimate the pace of profit growth deceleration and are inclined to regard the robust profit growth of enterprises in previous years as a long-term trend, consequently assigning overly optimistic valuation expectations. This constitutes the primary and key factor fueling asset bubbles.

Second, whenever a technological revolution arrives, after observing a handful of enterprises reaping the dividends first, investors tend to subjectively assume that all players in the same sector can replicate such profit miracles—yet reality often belies this assumption. Technological innovation is inherently characterized by significant barriers to entry and first-mover advantages; not all market participants are capable of replicating core technologies. Even if some enterprises manage to achieve technological imitation, they will most likely have missed the window of opportunity to seize market leadership. Coupled with the intensifying industry competition and the continuous narrowing of profit margins, latecomers are simply unable to match the development heights of leading enterprises. Nevertheless, investors often overlook this objective law, clinging to the expectation that small and medium-sized enterprises can also replicate the path to success. This in turn drives an overall rally in related concept stocks, ultimately causing asset bubbles to expand further.

Third, economic data during a technological revolution cycle can easily mislead the Federal Reserve’s policy judgments. Under the conventional policy framework, the Fed’s monetary policy is anchored in macroeconomic fundamentals: it initiates an interest rate hike cycle to curb inflation when the economy overheats; and it adopts interest rate cut measures to stabilize employment and boost growth when economic growth momentum is insufficient. However, this policy logic may fail in the special phase of a technological revolution. Technological revolutions drive a substantial leap in social productivity. Following conventional regulatory thinking, the Fed should theoretically raise interest rates to cool down the economy. Yet in the early stages of a technological revolution, productivity gains often do not coincide with a rise in inflation. On the contrary, technological iteration tends to lead to structural layoffs. This combination of rising productivity, low inflation and employment pressure instead forces the Fed to implement interest rate cuts. The overlap between a buoyant economic environment and accommodative monetary conditions of low interest rates creates a perfect breeding ground for asset bubbles.

The Expansion and Burst of the Bubble

In fact, starting from 1998, the internet bubble had already entered its late stage, and the prices of related assets subsequently surged along an irrational upward trajectory. Two landmark events took place during this period, which fully testified to the market’s frenzy: First was the IPO of Broadcast.com, a streaming media company. Its stock price soared by as much as 250% on the first day of trading—a record-breaking gain that was simply unprecedented at the time. Second was the business expansion announcement of Amazon. Back then, Amazon planned to leverage the channel advantages of its internet platform to add CD sales to its existing book retail business. Upon the release of this news, Amazon’s stock price skyrocketed by 200% within just a few weeks. These two incidents are enough to show how far the speculative mania had gone in the market back then. This irrational frenzy in the market ultimately triggered the Federal Reserve’s vigilance. In May 1998, multiple Fed officials publicly called for an interest rate hike cycle, aiming to timely curb the further expansion of the asset bubble. Objectively speaking, if the Federal Reserve had actually implemented the rate hike back then, the internet bubble might have been effectively contained in its infancy.

However, events unfolded in a way that ran completely counter to expectations. In August 1998, a black swan event struck out of the blue—the full-blown outbreak of the Russian debt crisis. Its negative impacts continued to escalate, delivering a direct blow to global capital markets led by U.S. equities. More crucially, several hedge funds, Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) being the most prominent example, held large positions in Russian bonds at the time. The precipitous plunge in bond prices pushed these institutions to the brink of bankruptcy, and their risk exposure even threatened the stable operation of the U.S. financial system. To safeguard financial system stability, the Federal Reserve resolutely shelved its interest rate hike plan, executed a 180-degree policy U-turn, and shifted to interest rate cuts instead. From that point onward, asset bubbles in the U.S. stock market completely slipped the leash and entered a phase of accelerated expansion. In the subsequent two months, the Nasdaq Composite Index surged by as much as 60%, and a host of internet concept stocks spiraled into irrational euphoria. Take Amazon for instance: its stock price skyrocketed by a staggering 600% in a mere three months. The IPO market at that time reached a level of frenzy that defied all market expectations: a chat room company named TheGlobal.com saw its share price surge tenfold on its first day of trading. The internet bubble was thus completely out of control and continued to balloon in scale. It was not until 1999 that mounting inflationary pressures forced the Fed to launch the long-awaited interest rate hike cycle. Under the impact of successive rate hikes, this long-brewed super internet bubble finally burst in 2000. The Nasdaq Composite Index plummeted 77% from its all-time high, countless internet companies subsequently filed for bankruptcy and liquidation, and ultimately faded into oblivion.

Looking back at the current market environment, the asset bubble in the artificial intelligence sector shares almost the identical underlying mechanics with the internet bubble back in the day. The core difference between the two lies in the triggers that prompted the Federal Reserve to postpone interest rate hikes and allow the bubble to inflate: back then, it was the shock of the Russian debt crisis, whereas today, it stems from the persistent weakness in the job market. Judging from the recently released nonfarm payroll data, the job market has remained in the doldrums, with the unemployment rate even climbing to 4.6%. Against this backdrop, a consensus expectation has taken hold in the market: there is still room for two more interest rate cuts in the current easing cycle, and the Fed will most likely not put the topic of rate hikes on the agenda until August 2027. This means that if market forecasts align broadly with the actual policy trajectory, there will still be a window of nearly two years from now before the Federal Reserve moves to rein in the bubble. By then, the asset bubble in the AI sector may have inflated to an irrationally extreme level. Once a policy shift triggers the bubble to burst, the sharp market crash that unfolded in the late stages of the internet bubble could very well repeat itself.

Conclusion

In summary, the current AI market rally bears striking similarities to the internet boom of the late 20th century—both are asset bubbles fueled by technological revolutions. From a policy regulation perspective, the Federal Reserve should have intervened in a timely manner at the first signs of the bubble and nipped it in the bud.

However, constrained by external shocks and internal fundamentals—back then, the Russian debt crisis; today, the persistent weakness in the job market—the Fed has been forced to postpone its interest rate hike cycle. Based on the above analysis, we can draw the following conclusion: over the next two years, the AI sector is likely to repeat the same fate as the internet bubble, spawning a large-scale asset bubble. For investors with exposure to the U.S. stock market, it is imperative to remain highly vigilant against the irrational expansion of this bubble and make investment decisions with prudence.